Graduate student Gennie Thi Nguyen’s old neighborhood was flooded by as much as nine feet of water after Hurricane Katrina pounded the Gulf Coast in August 2005. For Nguyen, like other Vietnamese Americans of her generation who grew up in New Orleans, the destruction of vast areas of her city became a trauma shared with parents and their generation, and opened up new areas of communication, she said.

Nguyen was an undergraduate at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana, when Katrina struck. She remembers trying to call her parents, “but all the cell towers were down so I couldn’t get through.” So she tried calling her four older sisters to see if they knew anything through their social networks—like her, they were all living outside the New Orleans area. Her mom had gone to a wedding in California, she learned. Her father, who works on oil rigs on the Gulf Coast, had evacuated to Houston with his friends.

The hurricane and subsequent flooding constituted the worst natural disaster ever to hit the United States. It came almost exactly four years after the destruction of the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York City, but federal response could not have been more different.

While most media and scholars focused on the anti-Black racism evident in the official response, Nguyen did her fieldwork among Vietnamese Americans, conducting interviews and doing intergenerational comparisons as a participant-observer. She looked at how two generations of Vietnamese women responded to social traumas, and how gendered identities are historically produced.

A master’s student in anthropology, Nguyen grew up in the Versailles area of New Orleans East, a neighborhood that includes the densest population of ethnically Vietnamese people outside of Vietnam. Versailles is not so much a place as a state of mind, she explained. Eighty percent Catholic, the area is “like a snapshot of Vietnam put in America,” she said, adding: “Katrina forced the younger members of the community to think about their identities and who they are. They live in an ‘in-between space’ that really constitutes home.”

Her parents and their generation were no strangers to disaster and its aftermath, having fled from North to South Vietnam, survived their “civil war,” and evacuated Vietnam after the fall of Saigon in 1975. In October, barely a month after the hurricane, they began returning to their New Orleans neighborhood.

“The older generation equated it with being back in the refugee camps, waiting in line for food. Being there after Katrina to experience it with them has some kind of connection ‘emotionally’ as to what it means to be a refugee,” Nguyen said. She sees previous refugee experience as a factor in the rapidity and extent of return. The return rate of Vietnamese Americans a year and a half after the storm was 85 percent, she said, compared to other groups whose return rate is less than 50 percent.

“We rebuilt our community centers faster than anyone else, opened our centers to other groups, brought diverse groups together. But while the media always paints the Vietnamese people coming back as a success story, a model minority myth, in reality the community is still struggling to rebuild basic infrastructure such as health care, education, public safety, and language access. Materially, they still lost everything; they came back to the same state of a lack of electricity; many things still have to be gutted. Almost four years after the storm, they haven’t rebuilt roadways and streets,” Nguyen reported.

After graduating from Ball State, Nguyen returned to New Orleans during the summer of 2007 and worked for the nonprofit organization Mary Queen of Vietnam Community Development Corporation, whose mission is “to rebuild the Vietnamese American community in New Orleans East and to contribute to the rebuilding of a more equitable New Orleans.”

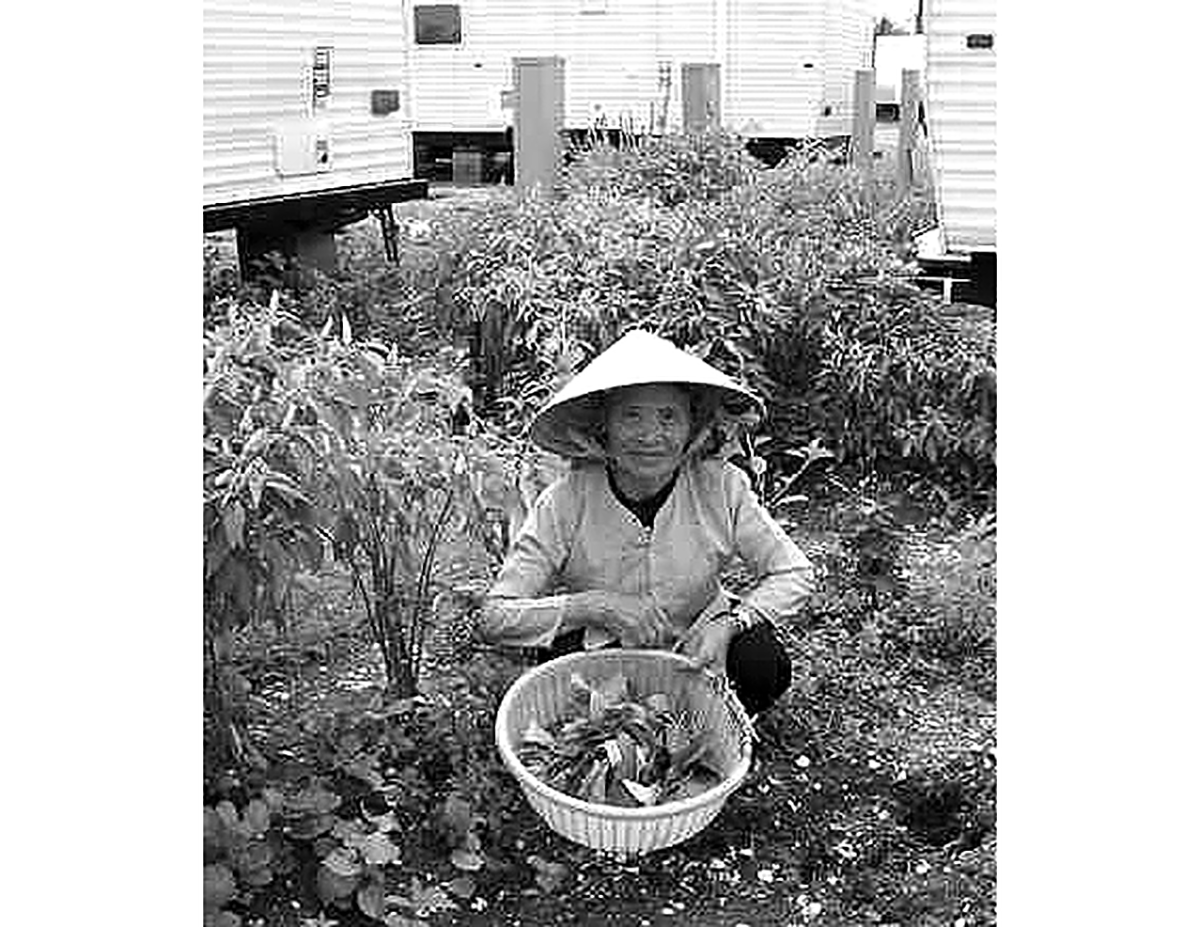

“This nonprofit organizing work is mostly a second generational action, which has to do with cultural competency about the American bureaucracy and having a higher educational status than our parents,” Nguyen said. “After the storm we found out the mayor had reopened a landfill less than a mile from the community; it was unlined and wasn’t protecting the local community against toxins from hurricane debris. We worked with the Sierra Club, did testing and showed that leaching was affecting the same groundwater that flowed into the canal that the older generation was using to water their gardens. We organized the community going to town hall. It was a way of being able to provide social service to the community. For the first time, my father actually understood what I want to do with my life—being involved in community organizing and cultural studies.”

—Alice Evans interviewed Gennie Thi Nguyen in May.