by Molly McBride, PhD Candidate Department of Anthropology

At the last rehearsal of Sistrum’s 2020-2021 season, we sang through our repertoire as a celebration of what we accomplished over Zoom rehearsals in the past nine months. It was also a coda orienting the women’s chorus toward the future, a “dress rehearsal” for a time when in-person concerts might be possible. One moment of this rehearsal, when we sang “I Have a Voice,” encapsulated the essence of my ethnographic research with the group. Meg, the chorus director, broadcasts a recording of “I Have a Voice” for us to sing with; on Zoom, each singer is muted and we sing along with the recording. From the start I have trouble finding my part in this challenging piece and I attempt to lipread by intently watching other singers, hoping to follow along even if a beat behind. We arrive at my favorite part, only eight measures with a repeating refrain over cascading melody: “Thunder catches my heart, thunder fills my lungs.” Almost immediately emotion overtakes me. Tears well and fall from the corners of my eyes and my throat croaks out the lyrics. I am often moved to tears when singing with Sistrum—uncharacteristically, I might add—but this time was different because I realized how thankful I am to have been part of Sistrum during the COVID-19 pandemic. Toward the end of the song, the recording cuts out and confusion and concern dawn on several faces. We are all lost without the music but eventually it returns, and we finish the song together…mostly.

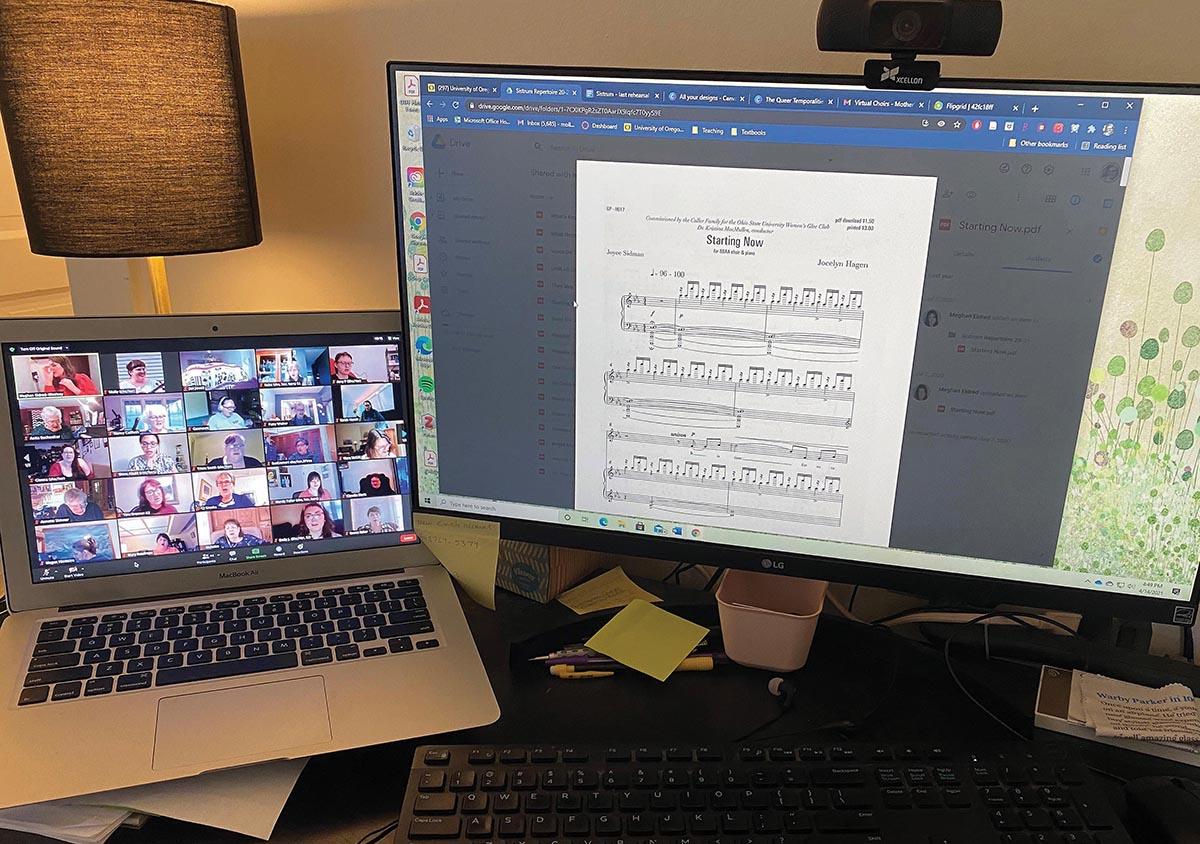

My research with Sistrum, a women’s chorus from Lansing, Michigan, unfolded in surprising ways over the past year. Supported by a CSWS Graduate Student Research Grant, I had originally proposed to look at the sexual politics of the chorus: how gender, race, sexual orientation, and class are performed in the chorus, both at an individual level and at a group level, as the chorus brings together many voices into one. With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was difficult to reconceptualize my project. Luckily, Sistrum pivoted to Zoom rehearsals, so I, too, pivoted to digital ethnography. Out of necessity, my research focus changed from issues of identity to the group’s navigation of the pandemic and how their activities, which heavily rely on in-person interaction, went digital. As with any internet-mediated encounter, rehearsals were often affected by technology issues: lags between video and audio, audio dropping, video freezing, and the like. These disruptions of time and connectivity, along with the general rupture of time caused by the pandemic, were at the forefront of my ethnographic experience with Sistrum.

I use temporality, and in particular queer temporalities, to examine Sistrum’s queer history, tempos of Zoom, and creative responses to the pandemic. Founded in the 1980s in Lansing’s vibrant lesbian community, Sistrum enacted separatist principles from lesbian-feminism that was predominant at that time. Through interviews with founding and current members and participant observation of rehearsals, I saw traces of lesbian-feminism in the group’s current politics, along with the negotiation of queer politics, white privilege, and anti-racism. Over Zoom, singers navigated tempos of connectivity and musicality. Often rehearsals were mired in disconnection, but we found different forms of sociality on Zoom and translated some traditions, such as singing to new members at the start of a semester, to digital contexts. The regularity of meeting every Wednesday provided a consistent social and creative outlet where we could collectively grieve and share anger and joy. At the direction of Sistrum’s artistic director and board, we started producing music videos as a creative response to the constraints of the pandemic. One video, “SIGNS,” plays with temporality through remixing old and new footage of Sistrum performing the song. This remix signifies Sistrum’s past politics, current pandemic reality, and visions for a more just future.

As I look to my own academic future, I hope to soon publish my research as a journal article. I am currently preparing an article focusing on the different temporalities mentioned above and hope to elicit feedback from Sistrum members in the spirit of reciprocal ethnography. I presented this research at the 2021 Western States Folklore Society Conference in April and at the 2021 Société Internationale d´Ethnologie et de Folklore Congress in June. This CSWS-funded research is exploratory for my dissertation, and though things will look quite different when I begin dissertation research in 2022, working with Sistrum over Zoom has informed how I am planning out my topic. First, in learning about the robust history of LGBTQ+ people in Lansing, Michigan, I am recommitted to the importance of place, memory, and ecologies of community. I hope to explore several different queer communities in Lansing through their place-making and -remembering activities and the political commitments of each. Second, I hope to also examine the digital mediation of queer communities. After so much time spent online and on social media, I realized the importance such technology has in connecting people and in shaping identity.

Though rehearsals have ended for the summer, I continue to reflect on the work of ethnography during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. I developed a real attachment to the group and its members, and in part I think this is because of how they have affected me. Sitting alone in my apartment, I began to use my voice in new ways and realize that, as the song goes, I have a voice. I am continually learning how to use my voice and the thunder that fills my lungs in ethnography and everyday practice, learning when to speak out and when to listen.

—Molly McBride is a PhD student in Anthropology. She received a 2020-21 graduate student research grant from CSWS.