CSWS events have always served as informal sites for networking, support, and mentorship among women faculty and graduate students across campus. When the pandemic shut down our regular programming last year, the Women of Color (WOC) Project filled this need with a virtual books-in-print event series celebrating recent monographs by WOC faculty affiliates.

The WOC Project has been a special project under the auspices of CSWS since 2005. Over the years it has evolved as a vital research, mentoring, and support network for WOC faculty who often find that they are the only one of their kind in their academic units and are seeking both mentorship and community from fellow colleagues. Activities include writing workshops for tenure and post-tenure research, grant-writing workshops with expert consultants, small grants for individual projects and events, and a fellowship competition for summer research support.

Affiliate faculty also have been sought out by graduate and undergraduate WOC who want to emulate the group and be mentored by WOC faculty as they build their own networks for professional success.

The WOC Books in Print series featured four faculty—Ana-Maurine Lara, Kemi Balogun, Leilani Sabzalian, and Tara Fickle—who have been mentored through the WOC Project and who, in turn, have mentored WOC graduate students in their fields. Below are some personal reflections by current graduate students who have been impacted by the work and words of these faculty.

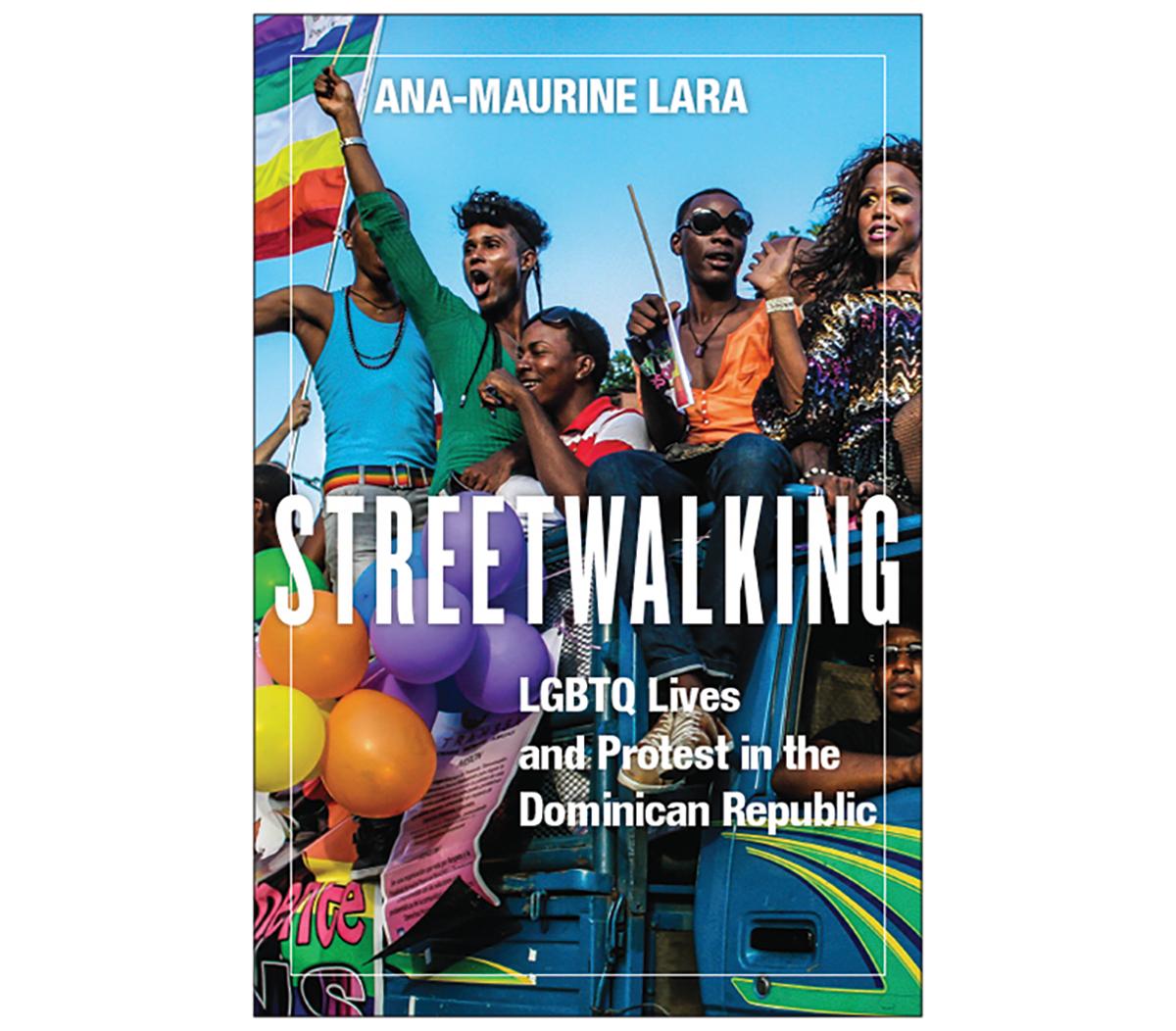

Ana-Maurine Lara, Streetwalking: LGBTQ Lives and Protest in the Dominican Republic and Queer Freedom : Black Sovereignty

Reflection by Polet Campos-Melchor

Intricately woven, Ana-Maurine Lara’s book talk on Jan. 29, 2021, was a double celebration of her twin books, Streetwalking: LGBTQ Lives and Protest in the Dominican Republic (Rutgers University Press, 2020) and Queer Freedom : Black Sovereignty (SUNY Press, 2020, winner of the Ruth Benedict Prize of the Association for Queer Anthropology, a section of the American Anthropological Association). Drawing on the Caribbean concept of sacred twins, these books show the implicit connections between Black and LGBTQ people globally and calls on readers to imagine, witness, and work toward freedom. During a pandemic that has disproportionately affected Black, Latinx, and migrant communities, these books serve as reminders to honor our communities without forgetting ancestors who also carved paths and teachings as lessons for our own journeys.

As I listened to Dr. Lara’s reflection on her research in the Dominican Republic and life in the U.S., I was moved by how her work expands on the concept of “reading” as a queer and ontological undertaking that she engages to weave in, out, and through her many roles as teacher, scholar, artist, and healer. Throughout her texts and in her talks, she refers to the past, present, and future as always being in conversation. This reference is a Black feminist practice and a tool she mobilizes for her readers to use in reading how and who we hold and carry with us in our work, daily life, and prayer. Dr. Lara has taught me and continues to teach me new possibilities for living, writing, and teaching as a whole person. She has taught me that I am a vessel for the knowledges of my relatives, teachers, and ancestors. The people, work, and prayers that I carry with me are for my protection, and are also my responsibility. She has taught me to weave my life and stories as she shares tools for doing such work.

—Polet Campos-Melchor, PhD candidate, Department of Anthropology

Oluwakemi Balogun, Beauty Diplomacy: Embodying an Emerging Nation

Reflection by Kiana Nadonza

As part of the CSWS Women of Color Books in Print Project, we gathered Mar. 5, 2021, via Zoom to celebrate Dr. Oluwakemi “Kemi” Balogun’s book, Beauty Diplomacy: Embodying an Emerging Nation (Stanford University Press, 2020). Dr. Balogun is a professor of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Sociology at the University of Oregon.

I am grateful to have met Kemi in my first year of graduate school. As a nascent scholar of beauty pageantry, I quickly realized that my research received visceral reactions of intrigue, confusion, and most surprising to me, dismissiveness. Not everyone seemed receptive to pageantry as a serious mode of scholarship, or the magnitude of the lens through which it offers a gateway into understanding a community’s politics and cultural practices. The first time we met, I was nervous to talk with an established scholar whose work I read and admired. At one point, I asked, “Do you ever feel some people do not take our research seriously?” Kemi’s quick, knowing smile broke the ice, and her reaction made me feel relieved and understood. I left Kemi’s office that day feeling much more confident, for although not everyone might immediately understand why our work is significant, what matters is the voices of the communities we work with and our commitment to standing by our research.

As my knowledge of beauty pageantry scholarship deepens, I appreciate Kemi’s contributions to the field even more. She is one of the few scholars producing contemporary studies on beauty pageantry in such nuanced manners, wherein pageantry cannot be confined to the hegemonic realm of academic discourse that dismisses beauty as inherently frivolous, or predicated solely upon the universal subjugation of women’s bodies. Rather, Beauty Diplomacy emphasizes the complexities and disjunctures of beauty pageantry, the material realities it produces, and its political implications within Nigeria. As Dr. Saraswati (University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa) astutely pointed out during the book panel discussion, Kemi “dares to ask bigger questions.” Beauty Diplomacy challenges us to re-envision how we conceptualize the relationship between beauty, power, and global politics.

—Kiana Nadonza, PhD student, Department of Anthropology

Leilani Sabzalian, Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools

Reflection by Roshelle Weiser-Nieto

Often when presenting professional development around equity, culturally relevant teaching, and ethnic studies/Indigenous themes, the teachers ask for tools they can use to put the work into practice. What do I actually do? What tools can I use? These are hard questions to answer because the work isn’t something you can walk into a classroom and do. It requires a shift in the lens through which we are looking at the classroom, curriculum, and the world. For anyone asking these questions, I love recommending Dr. Leilani Sabzalian’s book, Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools (Routledge, 2019, winner of the Outstanding Book Award from the American Educational Research Association). She wrote this book as an offering to all who work in the realm of education to capture lived experiences of Native students, families, and community and to offer interventions through survivance storytelling.

To describe the storytelling process as a mode of education, she cites a story told by Nick Thompson as cited in Basso: “When an individual isn’t acting right, he said, someone stalks them with a story, an act that may cause that person ‘anguish’ by thrusting that person into ‘periods of intense critical self-examination.’ Historical tales are valuable. They ‘make you think hard about your life’ and often, if a story goes to work on someone, the individual emerges more ‘determined to “live right”’ (Basso, 1984, p. 43).” By exposing the “persistent threat of colonialism and Indigenous erasure,” the goal is not just “to tell educators what to think or feel,” Dr. Sabzalian wrote the stories to give educators “‘the space to think and feel’ (as cited by Archibald, 2008, p. 134)” (p. 200). However, she also asserts, “These stories are not intended to provoke empathy or apologies. Rather my hope is that they provoke discomfort, indignation, and a sense of urgency and responsibility, here defined as a commitment to disrupting colonialism and teaching in service of Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty” (p. xviii). This is the power of this very important book, by reading the survivance stories within the pages, I hope each educator leans into the messages within and lets the stories resonate and impact their future teaching decisions.

—Roshelle Weiser-Nieto, PhD student, Critical and Socio-Cultural Studies in Education

Tara Fickle, The Race Card: From Gaming Technologies to Model Minorities

Reflection by Teresa Hernández

On May 7, 2021—at the beginning of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage month—Tara Fickle presented a discussion of her monograph, The Race Card: From Gaming Technologies to Model Minorities (NYU Press, 2019, winner of the American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation). In her project, Fickle brings together a number of fields including queer game studies and Asian American studies in her consideration of how gaming and gaming technologies utilize racial fictions to craft Asian American racializations and representations. By introducing “ludo-Orientalism” as a theoretical concept to engage “play,” she offers an analysis of Asian American identity in relation to games like Pokémon Go, poker, and mahjong.

As a woman of color, I had not deeply considered my own relationship to digital game play and its racial discourse. I came to Pokémon Go quite late, since its 2016 launch when my daughter and I started playing avidly during our afternoon walks last summer. Quickly we began to befriend gamers from East to West and to send gifts with in-game resources. However, the game also made evident the ways in which my own brown body was constantly surveilled in outdoor spaces and neighborhoods. To play, I had to be hyperaware of our environment and gendered positionings in a predominantly white space like Oregon.

At the end of the talk, a number of panelists drew connections between The Race Card and the increased violence in the U.S. on Asians and Asian Americans since the start of the pandemic in 2019. Fickle’s work shows that while these attacks may feel relatively new, they are reflective of a lengthy historical and political Western process that situates Asian and Asian American subjects within the violent rhetorics of myths like the “Model Minority.” The Race Card brings us to urgently consider how BIPOC move—even digitally—across racialized geographies, which reflect as much about our history as it does our collective futurity.

—Teresa Hernández, PhD candidate, Department of English