by Daisuke Miyao, Associate Professor, East Asian Languages and Literatures

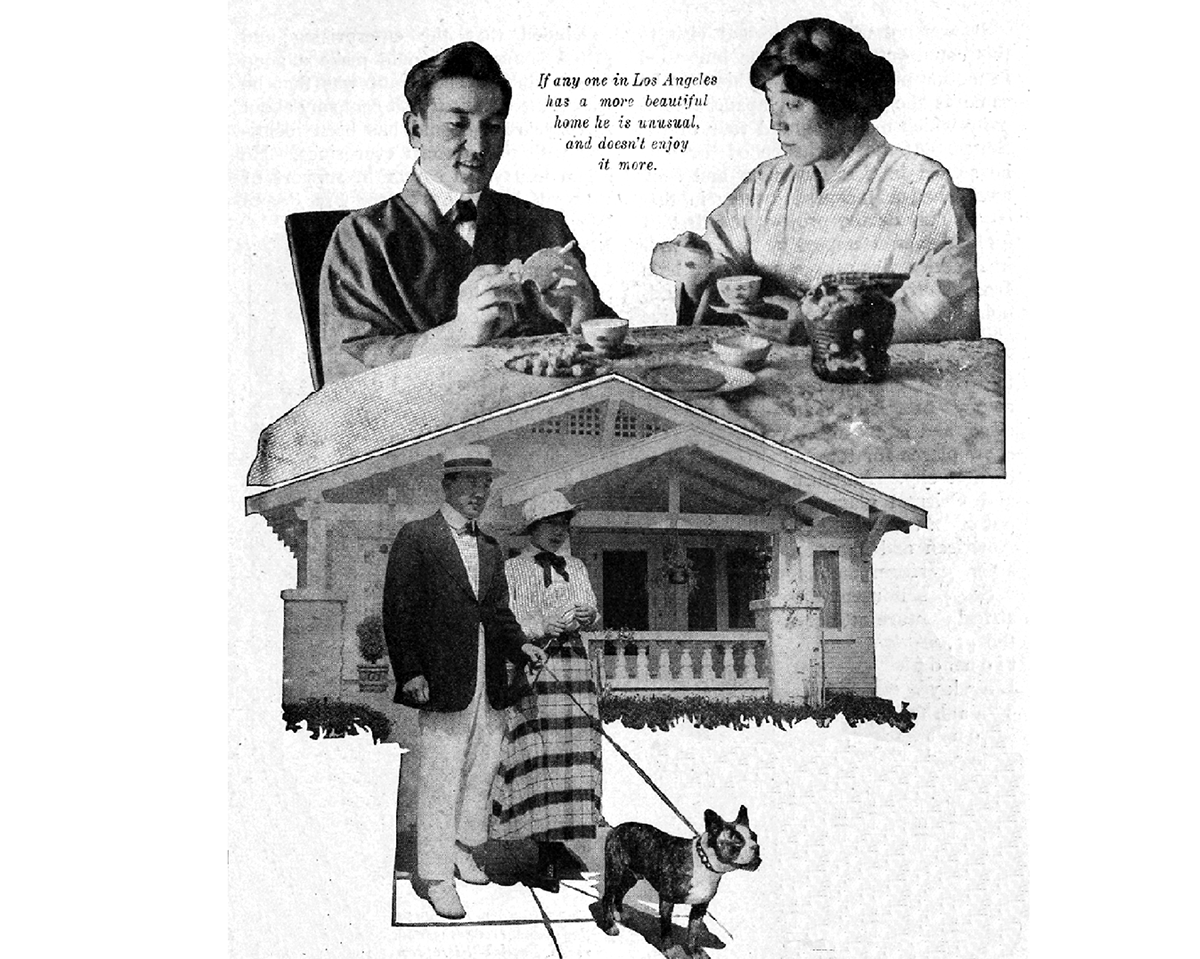

“It is no comparison. My mother had a much better acting skill than my father. My father’s acting was like, ‘I will show you how I can perform,’ but mother’s was so natural that we were able to watch it in a relaxed manner. My father knew about it very well.”1 The late Hayakawa Yukio, son of silent film superstar Sessue Hayakawa—the first and arguably the only Asian matinee idol in Hollywood—thus talked about his famous father and lesser-known stepmother, Aoki Tsuruko (1891-1961).

Yukio’s stepmother, known as Tsuru Aoki, was a renowned actress in early American cinema. In fact, Aoki was the first female Japanese motion picture actor. In Japan, the first female motion picture actor did not appear until arguably as late as 1918 when Hanayagi Harumi starred in Sei no kagayaki [Radiance of Life]. Before this film, the majority of female characters in motion pictures were played by onnagata, female impersonators in kabuki. Even in 1919, only three films out of about 150 films released in Japan during that year used female actors for female roles.2

Aoki’s stardom had different modes of reception and complicated meanings in varied geographical and historical sites. Initially formed in the early period of the American film industry, Aoki’s star image was rearticulated within various and contradictory political, ideological, and cultural contexts in the United States and in Japan during the period of public circulation. Within Aoki’s star image, there was a transnational war of images about “Japan,” “Japaneseness,” and “Japanese womanhood” among the actor herself, the filmmakers, and the various audiences. In the United States, despite her skillful acting, she became the first of the line of the Orientalist depiction of Asian women in Hollywood cinema, preceding such actors as Anna May Wong, Shirley Yamaguchi, Lucy Liu, and Zhang Ziyi. Japanese reception of Aoki’s stardom was completely different. Being a successful actor in early Hollywood, Aoki was a representative of modernism and Americanism.

The technology of cinematic lighting is one of the fascinating issues behind the emergence of female stars in Japanese cinema. Despite cinema’s innate status as a technological medium, scholars of film studies have focused more on analyses of stories and themes, and their relations to sociopolitical and economic contexts. Integration of theory and practice via analyzing technologies of female stardom will bring the discipline of film studies into the next stage.

When Aoki’s stardom was formulated in Hollywood, such photographic techniques as close-up, artificial three-point lighting, and soft focus were used for film stars both in their films and publicity photos in order to emphasize actors’ physical characteristics and convey sensual attraction and psychological states, which could go beyond the logic of the film narratives. While serving for the narrative clarity and consistency on one hand, these photographic techniques could also enhance the viewers’ sensory perceptions of materiality. Thus, contrary to onnagata, Aoki’s newness was based on the image of physical sexuality, using photographic technologies to enhance physical characteristics. Onnagata express their emotions in the movement of entire bodies, special configuration with other actors, and surrounding décor; long shots and flat lighting are more suitable to display their performance than close-ups with make-up and special lighting. The March 1917 issue of Katsudo Gaho, an early Japanese film magazine, for instance, juxtaposes a still photo of Tachibana Teijiro, popular onnagata in a 1917 film Futari Shizuka, and a portrait of Myrtle Gonzalez, a Hollywood star. While the latter is a sensual close-up of the actor’s face and naked shoulders in low-key lighting, dramatically highlighted with sidelight from the left, the former is a flat-lit long shot. Even though it is not clear how faithfully this still photo represents the actual scene in the film, this example implies how the Japanese film with onnagata emphasizes visibility of the theatrical tableaux in diffused lighting, rather than dramatically enhancing fragmented body parts or anything within the frame via lighting and make-up.3

The images of female stars in Japan, therefore, needed to skillfully incorporate Hollywood-style close-up and make-up in the tableaux-style composition and flat lighting of a kabuki convention. As such, Aoki’s professional achievement in the United States had a tremendous impact on the discourse of modernization of cinema in Japan. In the early 1910s, it was primarily young intellectuals—ranging from film critics and filmmakers to government officials—who began to criticize mainstream commercial films in Japan. They decried films made in Japan as slavish reproductions of Japanese theatrical works. They promoted a reform of motion pictures in Japan through the production of “modern” and “purely cinematic” films. Their writings and subsequent experimental filmmaking are often noted as the Pure Film Movement.

The Pure Film advocates criticized mainstream commercial Japanese motion pictures for being “uncinematic” because, for the most part, they were merely reproducing stage repertories of kabuki, most typified by the use of onnagata for female roles. Behind their words lay their irritation that Japan was far behind European countries and the United States in the development of motion pictures as a modern art form.4 They eventually intended to export Japanese-made films to foreign markets and affirm Japanese national identity internationally and domestically. These critics claimed that the only way Japanese film would become exportable to foreign markets was to imitate the forms and styles of foreign films. This rather contradictory attitude was in accordance with the political discourses of modernization in Japan. In order to obtain recognition as a nation in international relations, the Japanese government had adopted policies showing their movement toward modernization to Western standards since the late nineteenth century. This dual attitude of the Japanese government between modernization and nationalism was indicated by their slogan, “Japanese Spirit and Western Culture” (Wakon yosai). The film reformists insisted on the mutual development of Japanese cinema and Japanese national identity, using the American style of cinema.

These film reformists responded favorably to Aoki in terms of Americanism and nationalism. Her films were ideal products for the reformists because they used “cinematic” forms and techniques, especially continuity editing, naturalistic lighting and expressive pantomime, that were both understandable to foreign audiences and successful in the American market. Kinema Record journal noted, “[Aoki’s] eyes and mouth move as if she were European or American.”5 Katsudo Shahin Zasshi magazine placed a portrait of Aoki in its photo gallery section and noted, “Miss Aoki Tsuruko is a Japanese actress in the American film industry and she is one of the most popular stars…. We are fascinated by her sensual body and gorgeous facial expressions.”6 In early twentieth-century Japan, there was a “Caucasian Complex” in the discourse of physical appearance. Japanese bodies were considered shameful compared with well-built and well-balanced Western bodies. Aoki’s body presented a promising future for Japanese cinema that Western audiences would also appreciate.

Cinema has always been at the forefront of transnational culture form from the early period of its history. Aoki’s career in the global film culture reveals that stardom is an ongoing process of negotiation, a transnational negotiation, in particular. Tsuru Aoki’s stardom, which provided a template of a female stardom in Japan, reveals the historical trajectory of American images of Japan and of Japanese self-images in the world.

Daisuke Miyao received a 2010 CSWS Faculty Research Grant Award in support of his research on this topic. He is the author of Cinema Is a Cat: Introduction to Cinema Studies (Eiga wa neko dearu: Hajimete no cinema studies), Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2011 (published in Japanese).

Notes

1. Qtd., in Nogami Hideyuki, Seirin no o Hayakawa Sesshu [King of Hollywood, Sessue Hayakawa] (Tokyo: Shakai shiso sha, 1986), p. 62.

2. Saso Tsutomu, 1923 Mizoguchi Kenji Chi to rei [1923 Mizoguchi Kenji Blood and soul] (Tokyo: Chikuma shobo, 1991), p. 19.

3. See Hideaki Fujiki, “Canonising Sexual Image, Devaluing Gender Performance: Replacing the Onnagata with Female Actresses in Japan’s Early Cinema,” in Remapping World Cinema: Identity, Culture and Politics in Film, eds. Stephanie Dennison and Song Hwee Lim (London: Wallflower, 2006), pp. 147-60.

4. See Aaron Gerow, Visions of Japanese Modernity: Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, 1895-1925 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010).

5. Kinema Record 51 (November/December, 1917), p. 14.

6. Katsudo Shashin Zasshi 3, no. 12 (December 1917), n.p.