by Miriam Chorley-Schulz, Assistant Professor, German and Scandinavian Studies

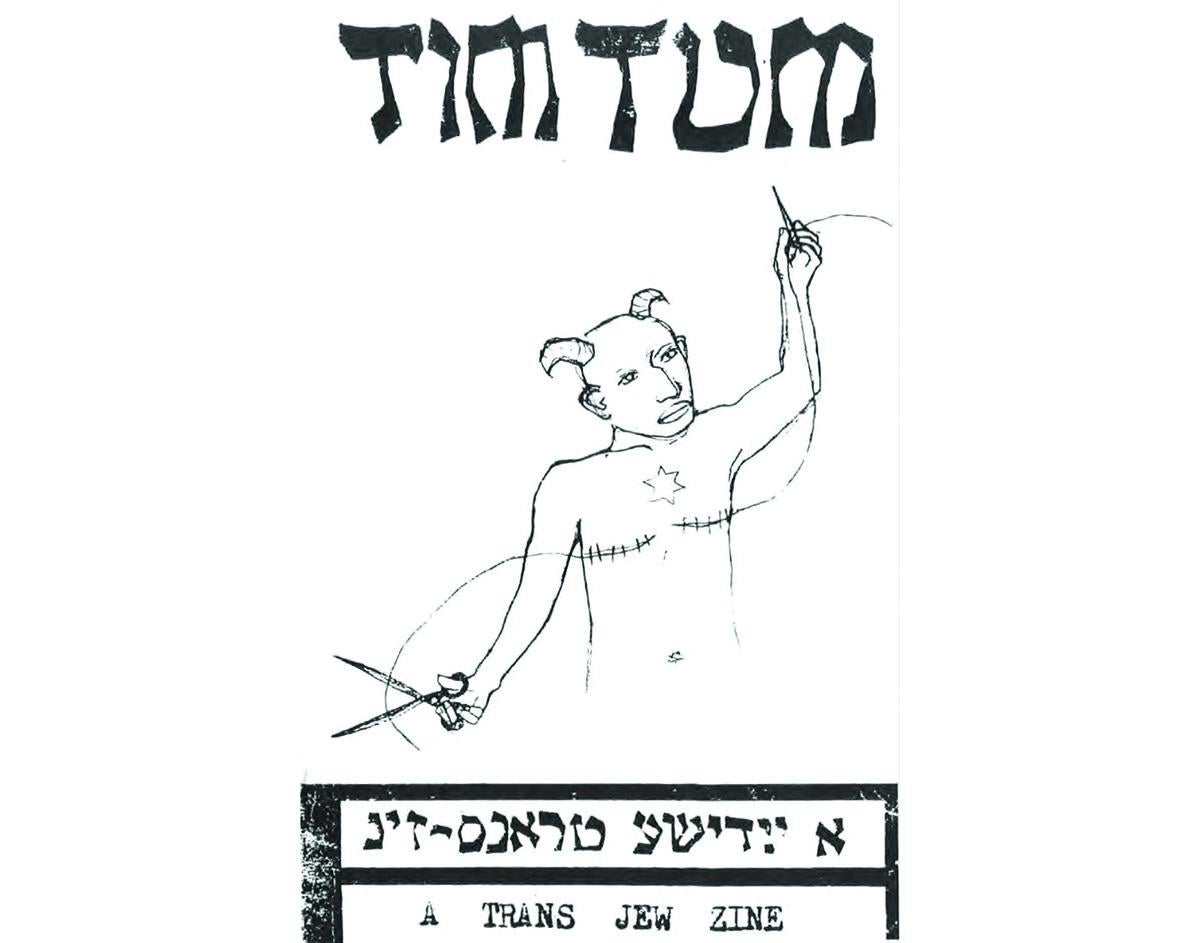

In their zine TimTum—A Trans Jew Zine (1999), Micah Bazant introduced an affirmative layer to the history of who is referred to in Yiddish as timtum (or tumtem). According to Bazant, a timtum is “a sexy, smart, creative, productive Jewish genderqueer.” This was not always the case.

Derived from the Mishnaic Hebrew tumtum whose Semitic root connotes “closedness,” a timtum, as Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert has shown, is originally treated in Rabbinic discourses as a not-yet-sexed person whose sexual organs may eventually appear or be revealed surgically.1 A twin figure of the much more commented on androgynos (person with both primary sexual organs throughout their lives), timtumim have been introduced by the Rabbis to put to the test the neat sex-gender binary they ultimately naturalized for Jewish collective reproductive purposes. Both categories demonstrate, however, that more ambiguous gender possibilities were at least theoretically grappled with in the making of Jewish law, even if dismissively and, for today’s eyes, potentially offensively so.

Timtum in Yiddish has different meanings, some closer to the original Hebrew than others. In dictionaries, translations include: hermaphrodite; asexual animal/person; and an androgynous person whose gender is hard to identify, folding the two Rabbinic sex-categories into one. Also, as Leo Rosten pointed out, the original legalistic subtext eventually got lost in Yiddish so that timtum today mostly describes “effeminate men” or a “beardless male youth with a high-pitched voice.” It also developed into an insult denoting “a total loss”—a slur for those not fitting into Jewish masculinist gender norms by being unproductive both intellectually and, we can deduce, physically. Bazant’s 1999 full embrace turns timtum on its head as a positive identity and point of pride, speaking to broader tendencies in the entangled histories of queerness and Yiddish.

Timtum is not only part of the Yiddish lexicon. Yiddish is timtumdik itself. Eastern European vernacular Yiddish, which brings Germanic, Hebrew, Slavic, and other linguistic elements into mutual relations, has similarly defied neat categorization for most of its millennium-long history. It has been derided and shunned as a result. A linguistic misfit, medieval and early modern Eastern European Jewish elites described Yiddish as “the language of women” or of “men who are like women” (i.e., unable to read Hebrew). With the advent of modern race science, Yiddish was derided as a symptom of Jewish “racial inferiority” mostly, but not exclusively, by non-Jews, inscribing Yiddish into the grammar of antisemitism and Jewish self-hatred respectively.

Simultaneously, certain Jewish national movements in the 19th and 20th centuries, conversely, embraced Yiddish as a tool of nation-building, but saw the need to “purify” and “masculinize” it. Many Eastern European Jews, however, became closeted in their Yiddish-speaking, predominantly communicating in other languages seen as culturally superior and linguistically more refined. Starting in the late 1960s, LGBTQ+ identit(ies) and Yiddish culture(s) have gradually been seen as natural allies—especially within progressive (primarily American) Jewish circles—not least because of a shared (without equalizing) experience of persecution: While the vast majority of Nazi Germany’s Jewish victims were Yiddish speakers, German fascists targeted the political left and those who they deemed “sexual deviants.” Today, whether in academic scholarship, LGBTQ+ performance art, feminist activism, or Yiddish language study groups, the fusion of queer and Yiddish has become a powerful symbol of resistance, pride, and politics.

This rough historical sketch raises important questions: How did we come from the Mishnaic misfit tumtum to the 19th-century Yiddish loser tumtem to the celebrated TimTum as we entered the 21st century? What is done to “queer” and “Yiddish” and what is hidden when these ideas are re-natured as always already dissident, always already progressive, always on the “right side” of history? Has Yiddish triumphed over its own history as sexy and smart, creative and productive, proudly genderqueer?

My current book project traces the messy histories that led to our current moment of “queer Yiddish pride” by queering the history of Yiddish itself. A Queer History of Yiddish examines how, since the 1800s, language, race, class, and gender have intersected to influence how Yiddish speakers have been constructed throughout modern history—and how they’ve lived and died in the wake of it. By returning to queer and trans theory’s original deconstructionist mission breaking down categories, questioning power structures, and exposing how identities—sexual, classed, racialized, linguistic—are built, policed, and normalized, I show how the history of Yiddish rhymes with modern queer histories: the pressures, desires, and failures to “fit” into dominant cultures, including fascistic ones, exist alongside practices of resisting and reimagining identity and community beyond traditional boundaries. Rather than treating Yiddish as a sealed-off heritage language or a nostalgic symbol of resistance, A Queer History of Yiddish explores Yiddish’s more uncomfortable histories rife with contradictions alongside its breathing radical potentials.

—Miriam Chorley-Schulz is an assistant professor and Mokin Fellow of Holocaust Studies at UO. She received a 2024 CSWS Faculty Research Grant for this project.

NOTES

1 Mishnah Yevamot 8:6; Yevamot 83b; Bava Batra 126b, in: Charlotte Elisheva Fonrobert, “Gender Identity in Halakhic Discourse,” Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women. 27 February 2009. Jewish Women’s Archive.