by Corinne Bayerl, Senior Career Instructor, Clark Honors College

With the support of a Center for the Study of Women in Society faculty grant, I was able to devote one month in summer 2021 to working on a chapter of a book manuscript on transnational debates over the legitimacy of theatre in Early Modern Europe. While the book as a whole examines the conflicts between supporters and opponents of the theatre across national boundaries and confessional divides, this chapter deals specifically with the role of female theatre practitioners who took on a leading role in the defense of public performances.

One argument common among opponents of the theatre at the time centered on the notion that theatre subverted normative gender roles and boundaries in a way that was considered dangerous for actors, spectators, and society as a whole. The common practice of having boys play women’s roles on stage was criticized, as was the appearance of female actresses on the theatrical stage. If the former led boys to assume “unmanly” behavior, the latter was depicted as being akin to prostitution. Support for theatre troupes by municipal authorities was castigated as a sign of cultural decadence, only heightened by the influence of foreign culture present on the stage, in the form of plays performed in foreign languages, or actors from abroad.

My curiosity about the role of women as active participants in theatrical battles was first peaked when I realized that only one single text authored by a woman figured among the two hundred texts compiled by a team of international scholars at the Sorbonne for a database on Early Modern anti-theatricality. While there was ample evidence, and scholarship, about the rise of actresses, about cross-dressing, and about the period’s fear of theatre as a tool of “effeminization,” there seemed to be scarcely any discussion of women intervening in the public debate about the legitimacy of the theatre. I wondered whether that lack of evidence accurately reflected a lack of diversity in a debate that appeared to be almost exclusively male-driven.

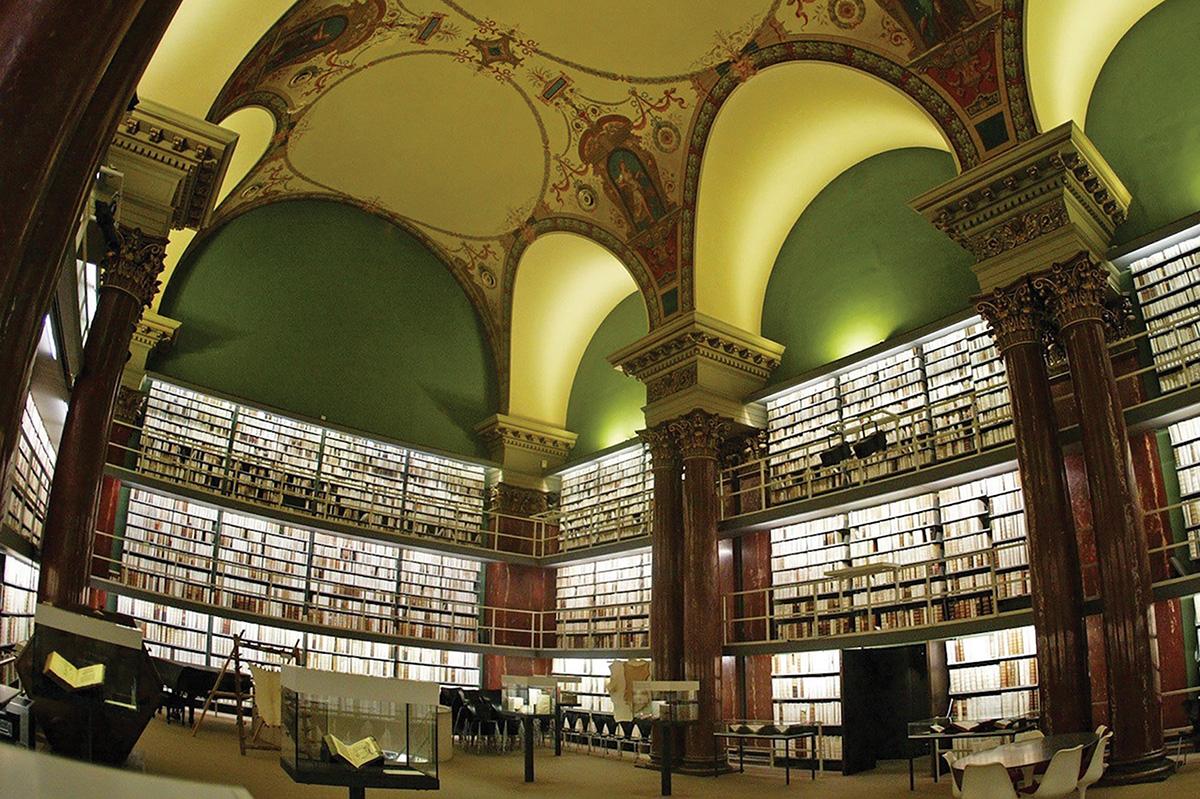

My search for female voices led me to the discovery of Catharina Velten, a highly influential Prinzipalin—a German term coined in the 17th century to designate a woman leading and managing a theatrical troupe. Velten toured with her troupe across Europe between 1700 and 1712, with her travels including regular visits to Scandinavia, Central, and Eastern Europe. Similar to the works of other itinerant theatrical troupes, the performances of Velten’s group are documented in small municipal archives and libraries that take time, money, and effort to access. In the extensive research I conducted on Velten in various locations in Europe, I managed to find letters, theatre programs, and repertories of plays of her troupe, which provided much needed context for the only publicly accessible, digitized text she authored: a 26-page treatise defending not only public performances in general, but specifically women’s rights to appear in public spaces and intervene in public debates.

Using Catharina Velten as a case study, my book chapter addresses the understudied role of female theatre practitioners in the debate about the legitimacy of the theatre in Early Modern Europe. Instead of dealing with actresses who have already been the subject of much scholarship, my chapter focuses on female directors of theatrical troupes in 17th- and early 18th-century Europe. The reason for the scarcity of scholarly studies of women leading theatrical groups has to do with the fact that these women often headed itinerant groups that were moving from one city to the next across Europe. The traces of their theatrical work and of their interaction with civic and religious authorities—which may be found in theatre programs, requests for play concessions, playbills, promptbooks, broadsheets etc.—are dispersed in various locations, including municipal archives in smaller towns across Europe.

In the context of the long struggle of theatres to assert their right to form part of civic life, women often played key roles: Not only did women write foundational theoretical texts in defense of the theatre, but they also found success as theatre practitioners—acting as playhouse managers, directors of theatre groups, and stage actresses. My study provides evidence that misogyny among critics of Early Modern theatre did not actually prevent stage practices from becoming more inclusive. Instead, anti-theatrical misogyny triggered responses from women who asserted their place in the theatre and defended the place of the theatre in civic life.

I would not have been able to make substantial progress on my book manuscript without the help of the Center for the Study of Women in Society. There are very few funding sources at UO that support the research of instructional non-tenure track faculty. For that reason, I am truly grateful to CSWS for recognizing the scholarly potential and contributions of NTTF in their fields of research. The prolonged focus on my research in summer 2021 turned out to be a key moment in the continued work on my book manuscript. The grant also helped me develop and submit a successful proposal for an external international grant that I was awarded at the end of 2021. I greatly appreciate CSWS’s support of interdisciplinary, feminist research, and in particular the support of NTTF scholarship.

—Corinne Bayerl is a senior instructor and core faculty member in Clark Honors College.