by Rhiannon Lindgren, PhD Candidate, Department of Philosophy

When one defines an activity as a “labor of love,” we are often referring to an experience that combines feelings of joy, difficulty, fatigue, and gratitude. While the labor of love is a sacrifice, the prepositional qualifier of “love” indicates the motivation for such a sacrifice. One labors out of a sense of love that is both inspiration and reward for a tiresome endeavor.

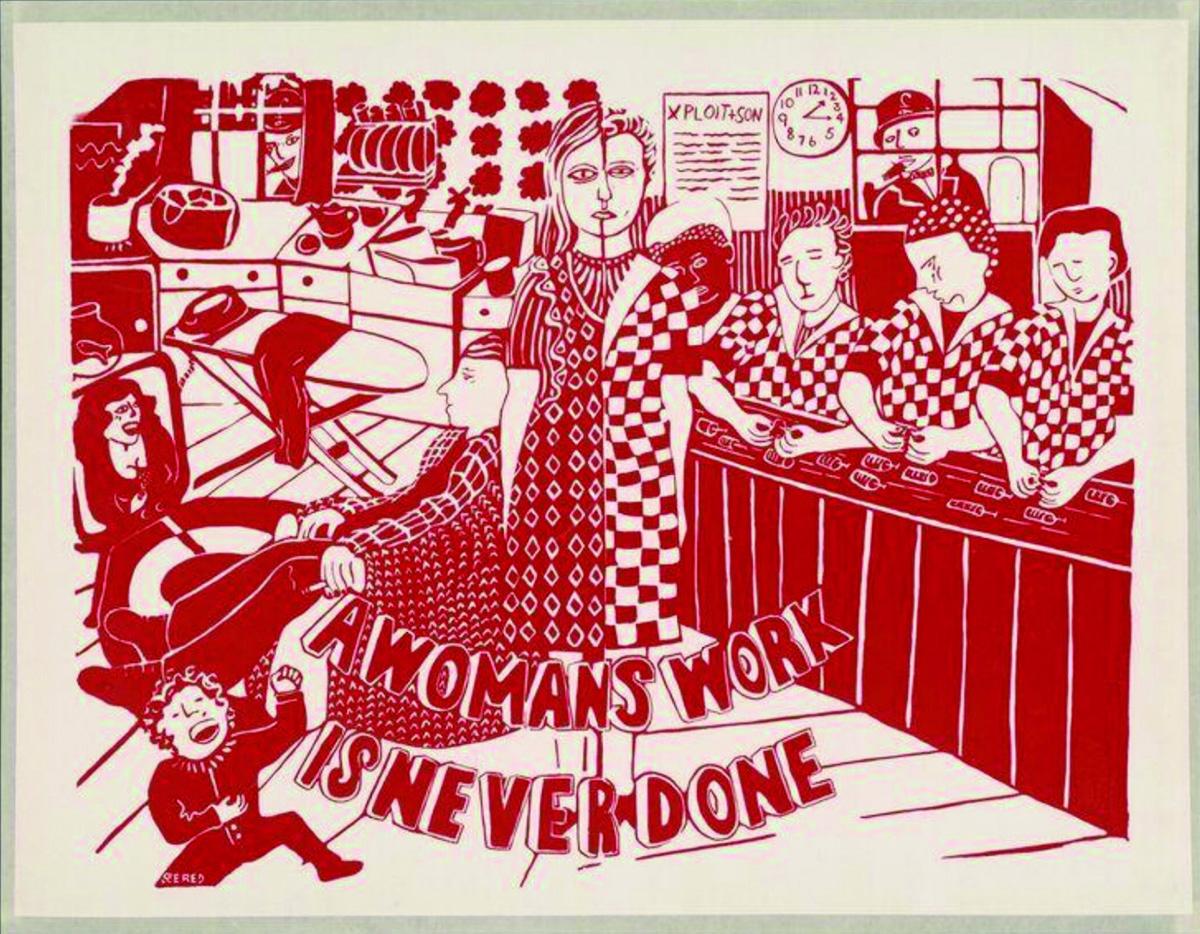

Feminisms in the US have taken a variety of positions toward such labors. With the onset of the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s, domestic labor—an exemplary form of human activity that comingles love and labor—was a primary target of feminist anger, resentment, and political struggle. As the goals of the women’s liberation movement shifted from liberation and toward an unflinching affirmation of femininity, the differences between men and women were emphasized even while equal opportunity and legal status became primary political goals (Echols 1989). At the turn of the twentieth century, the gutting of social services and public welfare recast basic human needs through an increasingly individualistic lens (Nadasen 2023). Labors of love never seemed more central and, increasingly, they were demanded of women in taxing and harmful ways.

Throughout all these phases of changing historical conditions, socialist and Marxist feminists have endeavored to articulate the role of domestic labor within women’s oppression and the varied social processes integral to the accumulation of capital. While in the 1980s the debate around domestic labor reigned supreme, Marxist feminists now emphasize an understanding of social reproduction as the practices and processes through which women’s relationship is determined under capitalist social relations (Bhattacharya et al. 2017; Vogel 2014).

Social reproduction includes the unpaid domestic labor of the housewife figure, like child-rearing and cleaning domiciles, but it also includes social institutions such as education, paid childcare, and healthcare as fundamental features of the overall reproduction and maintenance of human beings. Social reproduction theory (SRT) argues that a “hidden” circuit of reproduction was not adequately accounted for within Marxist theory and that this circuit largely defines the terms of gendered and sexual oppression underlying capitalism. Most importantly, SRT also claims that the level of social reproduction, or the access to essential reproductive resources that the working class has, is determined in part by the class struggles between the ruling and working classes (Vogel 2014).

Leftist, anti-capitalist struggles often under-determines the role of care as a site of political praxis. Even when community care is initially identified as a core objective of a political program or movement, the gendered and racial divisions that emerge in organizing caring labor often antagonize the internal practices of solidarity within radical political movements (Lindgren 2022). Often more “masculine” forms of public outrage and grief are classified as proper political activity while the quiet work of interpersonal repair or keeping people alive under conditions of extreme oppression are obscured from political discourse and analysis. Surviving under a capitalist social formation usually requires that individuals engage in some features of the production, distribution, and consumption of commodities in order to live. This means that politicizing survival cannot rely on a politics of purity, through which some types of individual and collective reproduction are classified as morally or politically righteous and others are demonized.

I came to notice these tensions within practices and labors of care through my experiences as an academic and a grassroots community organizer. As a worker in the feminized field of education, which happens to be a fundamental institution of social reproduction, I felt the way that discourses of care were deployed both to dissuade worker actions such as strikes and to justify the unreasonable workloads and expectations. Outside of academia, my political organizing activities often included discursive references to burnout, capacity check-ins, and self-care, but they rarely seemed structurally incorporated into group rituals or shared expectations. It always felt like an individual responsibility to attend to these needs, and as a person socialized as a woman, I got the feeling that I was not so good at identifying such things until they had gone from a moderate need to a severe one.

Since I found few frameworks available that politicized survival and the gendered caring processes through which survival is secured, I propose the concept of “reproductive struggle” in my dissertation to identify collective, conscious opposition in caring and reproductive labor to the distorted ways capitalism profits from our survival. This concept aims to generate interdisciplinary feminist scholarship on the ambiguity of care as both a transformative labor and one in which significant harm can be produced. I argue for a transnational horizon for future directions of feminist struggles upon which care, labor, and reproduction can become sites of antagonism to the maintenance of capitalism, imperialism, and white supremacy. Instead, such activity can become directed toward an emancipatory future.

—Rhiannon Lindgren received the 2024 Jane Grant Dissertation Fellowship for this project.

REFERENCES

Bhattacharya, Tithi, ed. 2017. Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression. London: Pluto Press.

Echols, Alice. 1989. Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975. American Culture. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Lindgren, Rhiannon. 2022. “The Limits of Mutual Aid and the Promise of Liberation within Radical Politics of Care.” Journal for Contemporary Philosophy 42(1): 3–17.

Nadasen, Premilla. 2023. Care: The Highest Stage of Capitalism. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.

Vogel, Lise. 2014. Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory. Historical Materialism Book Series. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books.