by Alisa Freedman, Associate Professor, Japanese Literature and Film, Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures

Between 1949 and 1966, at least 4,713 Japanese students studied at American universities with the best-known fellowships at the time—GARIOA (Government Account for Relief in Occupied Areas [1949 through 1951]) and Fulbright (established in 1952)—along with a few private scholarships.1 This group included 651 women. Among them were future leaders in fields as diverse as literature, medicine, economics, athletics, and political science.

Yet the names of these women have been omitted from Cold War histories, accounts of women and travel, and discussions of the formation of academic disciplines and jobs. Accounts of women and travel have focused on the Meiji period (1868-1912) or the 1990s and after, skipping the 1950s and 1960s. For example, much has been written about Tsuda Umeko, who attended Bryn Mawr College (1889-1892) and founded Tsuda College (1900).2 Field histories have lauded the “founding fathers” of Japanese Studies, including Edward Seidensticker and Donald Keene, whose translations created the American canon of Japanese literature. Using interdisciplinary research premised on personal interviews, memoirs, and institutional records, my CSWS project records the accomplishments of the “founding mothers” and shows how they have fostered generations of scholars. A handful of women have written memoirs about what they consider most meaningful about their experiences abroad and how educational exchange shaped their life courses.

These women’s story is one of history, memory, and empowerment. It has emotional meaning to me: it was inspired by my mentors and bridges the places I consider home: Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Tokyo. I focus on Japanese women who came to the United States under scholarships, rather than with personal sources of funding. These grants represent a belief in the power of education to shape international relations, a notion not as prevalent today. I chose the timeframe of 1949 to 1966 because of the start of the GARIOA, Japanese education reforms after 1947, the peak in Japanese study abroad students, and the liberalization of Japanese overseas travel in 1964. This was a time when Americans were interested in Japan for political and cultural rather than financial reasons. Japanese things, from sukiyaki restaurants to Zen Buddhism were in vogue because they seemed “exotic.” It was before Toyota and Sony became common names and students studied Japan out of interest in economics (1980s) and popular culture (1990s and beyond).3

These young scholars lived within a nexus of change, when the United States was rising in international stature and Japan was reemerging in a different form on the international scene as an exporter of new technologies, and as an American ally against Communism. They came after the U.S. internment of Japanese Americans (1942-1945) and after women received the right to vote in Japan in 1946.

These youths who experienced hardships of World War II in Japan were among the first people to travel abroad after the war. Foreigners were not permitted to visit Japan right after the war, unless working for the Occupation. The Occupation authorities granted international businesspeople entry in August 1947. They allowed foreign pleasure travel in Japan from December 1947 and, in October 1950, Japanese overseas travel for business. (The first Japanese groups to do so were sporting teams.) Starting in October 1951, Japanese companies could pursue foreign trade. Under the Passport Law of 1952, Japanese citizens were issued passports valid for one overseas trip that needed to be taken within six months. Travelers could circumvent this restriction by having a guarantor living abroad who could promise foreign currency. Overseas travel was liberalized in April 1964, the year Japan hosted the Summer Olympic Games, in part to reduce fictions between Japan and other nations as trade surpluses were mounting. The amount of money Japanese travelers could take abroad was limited to around $500.4

Just as travel was cost prohibitive for ordinary people, few women could afford to attend higher vocational colleges or universities, particularly before the 1947 Fundamental Law of Education (Kyōiku kihon hō). The opportunity to study abroad was open to a tiny number of women born under certain family financial circumstances. Women’s access to higher education was also hindered by beliefs that women’s life courses should prioritize marriage and motherhood. At this time, the social and political significance of the housewife was promoted through education and such popular media as newspapers.5 Many women who received scholarships after 1949 came to the United States for graduate school and planned to pursue careers. Especially before 1947, the few Japanese women’s colleges established in the early twentieth century were generally equivalent to vocational schools or junior colleges. A prime example is Tsuda Joshi Eigaku Juku that specialized in English and became Tsuda Juku Daigaku (Tsuda College) in 1948, the alma mater of many scholarship recipients. References to English were removed from the name in 1943 during the war with the United States.

Between 1949 and 1951, GAROIA, financed with money Japan had paid as a war debt, provided a total of 787 Japanese students the chance to study at American universities. The largest cohort was in 1951: 469 scholars with 162 women among them. These young scholars lived in areas most tourists did not visit, for many universities were in remote locations.

The Fulbright Fellowship, established in 1946, was funded by war reparations and foreign loan repayments. In 1952, after the Occupation had ended, the first cohort of seventeen American scholars came to Japan. That year, thirty-one Japanese students went to the United States. The Fulbright program was available to Japanese women from the start. For example, in 1952, the largest cohort to date (324 recipients) included forty-five women. Numbers of recipients dropped significantly after 1968. Starting in 1955, the Fulbright was open to all fields of study, but budget cuts in 1969 forced the discontinuation of grants in natural science, arts, and teaching. Art funding restarted in 1972, the year journalism was added. The Japanese government began to share costs in 1979, and private contributions began in 1981. The Fulbright Grant supported one year of education; many recipients extended their time abroad through private grants.

To provide a different ideological perspective, I would like to elaborate on one private grant: the “American Women’s Scholarship for Japanese Women,” most commonly referred to as the “Japanese Scholarship.”6 The grant was established to promote gender equality and a model of Christian, upper-class life as experienced in suburban Philadelphia. The idea had its genesis in discussions between Tsuda Umeko and Mary H. Morris; Morris’s granddaughter Marguerite MacCoy served as the Committee Chair for most of the duration of the scholarship. The Scholarship Committee included Quaker women who had been to Japan, such as Elizabeth Gray Vining, a Newberry Medal winning children’s literature author who had tutored then Crown Prince Akihito (1946-1950). According to the scholarship constitution:

“[S]tudents who accept this scholarship do so with the understanding that the benefit derived from it is to be devoted to the good of their country women.”7 The expectation was that most recipients would return to Japan to work as educators. Unlike the GARIOA and Fulbright, the Japanese Scholarship paid for four years of university education and, if needed, preparatory study at a Philadelphia area finishing school.

The Japanese Scholarship funded a total of twenty-five women, twenty of whom attended Bryn Mawr College. The first sixteen recipients were schooled in Japan before the 1940s reforms.8 Applicants were nominated by their Japanese colleges to take the scholarship examinations, which included fields ranging from classical Chinese to English literature. When Maekawa Masako (Bryn Mawr, 1960, professor of English at Tsuda College and coauthor of two textbooks on English writing) took the examination in 1958, the essay topic was “The Role of Women in Society.” The first three women to pass were Matsuda Michi (Bryn Mawr, 1893-1899), who became the first principal of Doshisha’s Women’s School; Kawai Michi (Bryn Mawr, 1898-1904), Christian leader and founder of Keisen University; and Hoshino Ai (Bryn Mawr, 1906-1912), President of Tsuda College during the war.

The Japanese Scholarship included tuition, room and board, and the first-year’s allowance, but recipients needed to pay for their own travel to Japan. To help defray travel costs, two recipients also received Fulbright Fellowships: Maekawa (described above) and Shibuya Ryoko, the first graduate student recipient (Bryn Mawr, 1955-1958, English literature) and first to be educated under the post-1947 system. Because Japanese Scholarship Committee doubted her degree from Tokyo Women’s Christian University was equal to an American B.A., they made her repeat one year of undergraduate study at Bryn Mawr. She later worked as the wife of the Chairperson of the Board of Trustees of Mitsubishi Corporation. Recipients were expected to work during summer vacations. For example, Tanaka Atsuko (Bryn Mawr, 1953-1957, political science) assisted victims of the Hiroshima atomic bombing who were receiving treatment at a New York hospital. (Tanaka later served as the Chair of UNESCO Committee in Japan, among other posts.)

The Japanese Scholarship continued without interruption. During the war, Japanese American Marguerite Sakiko Nose Stock received the scholarship (1943-1945). In 1940, Yamaguchi Michiko, was forced to leave the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture (part of Temple University since 1958) in 1942, becoming the only recipient in the history of the scholarship not to graduate. As she stated in a 1996 interview: “In New York, all my personal belongings were confiscated. All the papers, even my notebooks taken in classes were taken. The botanic specimens which I had gone as far as North Carolina to collect and pressed myself, and to which my botany teacher had added the scientific names in Latin, were also confiscated. We Japanese used to put paper inside the collars of kimono and haori (coats) to make them stiff. Some old postcards used for this purpose came out.”9 The Japanese Scholarship had a strong impact on women’s advancement and Japanese culture, as four recipients became university presidents, fifteen professors, and others doctors, among additional prestigious jobs. The program ended in 1976, due to the expense of its upkeep. Also, its form of societal training had become outdated. It was succeeded by the Mrs. Winstar Morris Japan Scholarship in 1987.

Several recipients of GARIOA, Fulbright, and Japanese Scholarships became professors who counter the conventional narrative that postwar Japanese Studies in the United States was established solely by American men who worked for the U.S. military in Japan. Study of Japan in the United States is generally a postwar development that reflects the two nations’ political, economic, and cultural relationship. According to a 1935 study, twenty-five U.S. universities offered courses on Japan, eight of which taught Japanese language. With a few exceptions, faculty members teaching about Japan also taught about China. Only thirteen instructors surveyed knew Japanese language well enough to conduct research in it.10

Arguably, the U.S. military trained more Americans in Japanese language than universities did. For example, the Navy Japanese Language School started at Berkeley in the fall of 1941. In June 1942 it was moved to the University of Colorado because Japanese Americans (who served as instructors) were excluded from the West Coast and banned from serving in the U.S. military. It trained around 1,200 students, many of whom served as translators during the war. After the war, some worked for the military, held diplomatic positions, and became scholars, like Edward Seidensticker.11 The Military Intelligence Service Language School, which started in San Francisco and relocated to Minnesota, trained around 6,000 students.12 Other “fathers of Japanese Studies” were born to Christian missionaries and raised in Japan, such as Edward Reischauer, or came to Japan to be typists and reporters, like film scholar Donald Richie.

The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946), by the American Ruth Benedict, one of the only women included in accounts of Japanese studies before the 1980s, was one of the few books on Japan available in English. The book was based on wartime research and written by the invitation of the U.S. Office of War; it was translated into Japanese in 1948. The lack of texts meant that most Americans read the same books on Japan. Female study abroad students who became professors filled the gap of knowledge about Japan; they were a quiet, forgotten force behind generations of scholars and scholarship.

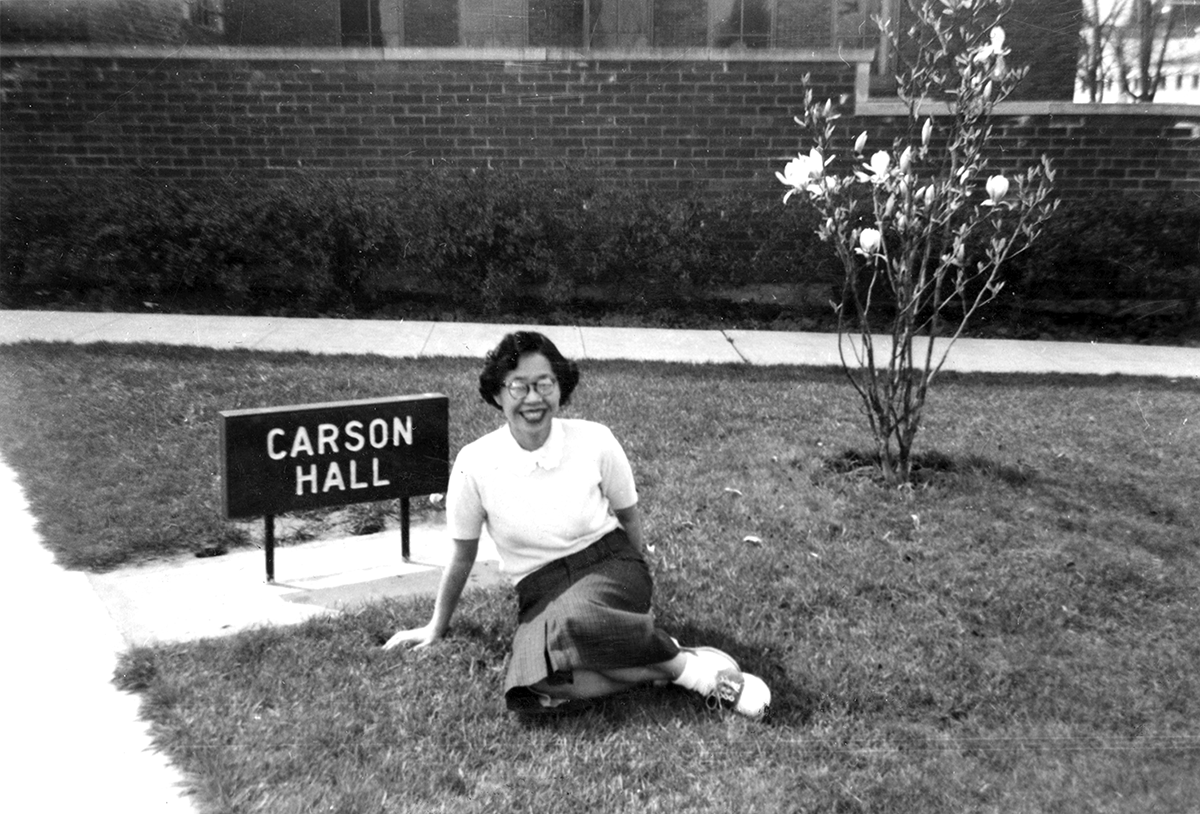

One “founding mother” of Japanese studies was University of Oregon’s own Yoko Matsoka McClain (1924-2011). Granddaughter of famous author Natsume Sōseki, Yoko entered the University of Oregon with a GARIOA grant in 1952, graduated with a B.A. in French (1956) and M.A. in Comparative Literature (1967). She became the university’s first regular Japanese language instructor in 1964 and led the Japanese program until 1994.13

In a memoir, Yoko admitted her reason for studying English: “While in high school, I was a big fan of American movies. Before war began with the United States, my sister and I went to see American films every Saturday night. I loved Tyrone Power, who to me was the most handsome actor in film, and I hoped to write a letter to him someday. I did not tell my mother, but that was why I studied English so intensively. And when you study a subject like that, you naturally come to like it.”14 She enrolled in Tsuda Eigaku Jukku in 1942, when students who studied English were subject to suspicion. In 1944 university president Hoshino Ai (Japanese Scholarship recipient) was ordered to send students to work in factories to make military airplane pistons. She decided it would be safer to set up a factory on campus, where students could work together in sturdy buildings. Classes were eventually canceled so that students could work fulltime. As a result, Yoko received only two years of schooling.

After the war, Yoko joined her family in Niigata Prefecture in northern Japan, where they had relocated to protect her younger siblings from the aerial bombings of Tokyo. There, she studied both typing and kimono construction, part of her lifelong interest in clothing design. After around two years, Yoko returned to Tokyo where work was plentiful for women who could speak English and type. She worked at the U.S. Armed Forces Radio Station and took the GARIOA examination at the suggestion of a colleague there. Yoko requested placement on the East Coast with the idea that she would arrive on the West Coast and then travel across country, but was assigned to Oregon. Yoko’s one-year fellowship was extended through the sponsorship of a Portland doctor who had been interned during the war. Having a guarantor made it easier for Japanese students to remain in the United States. To extend their stay, they merely needed to make a request to the State Department and give up the return ticket to Japan provided by GARIOA.

While earning a certificate to teach French, Yoko worked at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, where she met her husband (Robert McClain). When her husband was drafted, she accompanied him to Germany. When his unit was stationed in the state of Georgia where interracial marriage was illegal, he was discharged. (Miscegenation laws varied by state. The law was repealed in Oregon in 1951 but not until 1967 in Georgia.) Yoko became a working mother: while her son was a toddler, Yoko was asked by the University of Oregon to be a Japanese teaching assistant; she hired a babysitter and went to work. After completing her M.A., she became a fulltime Japanese instructor.

During her more than thirty-year career, Yoko published books to help Americans and Japanese understand each other and gave lecturers worldwide. For example, the Handbook of Modern Japanese Grammar (1981)—collection of her class handouts and published at the request of her students—has undergone more than twenty-one printings and has been an indispensible resource for students worldwide (including me).

A theme of Yoko’s memoir is that her achievements have been fortuitous and with thanks due to the encouragement of other people, reflecting her modesty, optimism, and flexibility: “When I think about it, the course of my life seems to have been charted not by my own decisions but those of others. I studied English in college on my mother’s advice, took a test to come to the United States at my friend’s urging, started teaching Japanese at a professor’s request, and published my first book at my student’s suggestion.”15

My project celebrates librarians who established collections of American and Japanese literature, in addition to the professors. For example, with Fulbright support, Takikawa Hideko earned an M.A. in English literature at Bryn Mawr College (1960-1963). She became a librarian and professor at Aoyama Gakuin Women’s Junior College, where she helped build the Oak Collection of Children’s Literature. Hideko has had a lifelong interest in letters. While a teenager, through Shōjo no tomo (Girls’ Friend) magazine, she found a pen pal in Boston, whom she visited while studying in Pennsylvania. Her life has paralleled her favorite book: Jean Webster’s 1912 epistolary novel Daddy-Long-Legs, which unfolds in letters written by a student at an elite American women’s college to her wealthy sponsor whose identity is hidden. In 2014 Hideko published a charming book of letters to her mother written while at Bryn Mawr. Now retired, she hosts readings groups in Tokyo on children’s literature written in English.

Scholarship recipients became pioneers in other fields, including gender studies and medicine. For example, Minato Akiko, retired professor and chancellor of Tokyo Women’s Christian University, wrote books comparing U.S. and Japanese feminist movements. She met her husband, also a Fulbright recipient, on the Hikawa maru en route to the United States, showing that study abroad affected other parts of life. (Her husband studied organic chemistry at University of Minnesota before earning a PhD at Harvard University.) Suzuki Akiko, who studied at Wayne State University and Columbia University Medical School, returned to Japan in 1963 as the nation’s first licensed occupational therapist. She founded two occupational therapy schools in Japan and was the first president of Japan’s Occupational Therapy Association.

Not all these women became academics. Toshiko Kishimoto d’Elia (GARIOA, 1951) became the world’s oldest female marathon runner, entering her first race at age forty-four in 1976, and continued running through her seventies. She came to the United States for training in special education not available in Japan and earned an MA in audiology from Syracuse University. Toshiko married an American and then divorced and became a single mother in 1955. Given the ultimatum by her parents to give the baby up for adoption and remarry a Japanese man, she decided to stay in the United States; she then taught at a school for hearing-impaired children in New York.

This small sampling of a large group of successful women demonstrates that study abroad students were instrumental in forging Japan-U.S. cultural exchange in the early Cold War era and in advancing women’s equality. They were cultural ambassadors receiving more media attention than the Japanese men who attended American universities. In addition to being bilingual and able to trade in cultural knowledge, they were seen as representing a peaceful, domesticated Japan. They show how women are often cast in roles of nurturers and mediators, and how women’s education is promoted as a tenet of democracy.

Since sending an email to female Fulbright recipients with the help of Japan-U.S. Educational Commission (JUSEC) during a summer 2015 research trip to Tokyo funded by CSWS, I have received a wealth of personal papers, books, photographs, memoirs, and invitations to meet by women eager to tell their stories. It is difficult to find information about women who did not have positive experiences. At a time when the housewife was being solidified as a middle-class ideal, many of these women became professors, authors, and translators who shaped the American field of Japanese studies and the Japanese field of American studies. Others entered professions that demand high levels of education. They uncover unexpected variety in women’s work and politics in the 1950s and 1960s.

—Alisa Freedman is an associate professor of Japanese literature and film, UO Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures. Much of her interdisciplinary work investigates the ways the modern urban experience has shaped human subjectivity, cultural production, and gender roles. Her CSWS funding for this project was drawn from the Mazie Giustina Endowment for Research on Women in the Northwest.

Footnotes

1. Private grants included those founded by alumni of women’s universities and by political organizations with often with intent of cultivating Japan as political and cultural ally. For example, female writer Ariyoshi Sawako studied at Sarah Lawrence University in 1959 with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation.

2. See, for example, Sally Hastings. “Japanese Women as American College Students, 1900-1941.” In Modern Girls on the Go, edited by Alisa Freedman, Laura Miller, and Christine Yano, 193-208. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

3. I thank Mark McLelland’s project on “End of Cool Japan” and my panel on “Exporting Postwar Japan: Japanese Business and Culture Abroad” at the 2006 Association for Asian Studies Annual Meeting for encouraging this line of thinking.

4. For more information on Japanese travel and tourism, see Roger March, “How Japan Solicited the West: The First Hundred Years of Modern Japanese Tourism.” ResearchGate, December 2006. Online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240622199_How_Japan_Solicited_the_West_The_First_Hundred_Years_of_Modern_Japanese_Tourism and “No Substitute for Overseas Travel,” Japan Times, January 6, 2014, online at http://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2014/01/06/editorials/no-substitute-for-overseas-travel/#.V1ot2Md6rGg

5. See Jan Bardsley. Women and Democracy in Cold War Japan. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

6. This section draws from a wonderful collection of archival materials, essays, surveys, and interviews compiled by four Japanese Scholarship alumni: Shibuya Ryoko, Uchida Michiko, and Yamamoto Yoshimi. Japanizu sukarāshippu: 1873-1976 no kiroku. (The Japanese Scholarship: 1873-1976). Tokyo: Bunshin shuppan, 2015.

7. Shibuya, Uchida, and Yamamoto, p. 211.

8. The first three women to pass were Matsuda Michi (Bryn Mawr, 1893-1899) who became the first principal of Doshisha’s Women’s School; Kawai Michi (Bryn Mawr, 1898-1904), Christian leader and founder of Keisen University; and Hoshino Ai (Bryn Mawr, 1906-1912), President of Tsuda College during the war.

9. Quoted in Shibuya, Uchida, and Yamamoto, p. 362.

10. Helen Hardacre. “Japanese Studies in the United States: Present Situation and Future Prospects,” Asia Journal 1:1 (1994): 18.

11. David M. Hays. “Words at War: The Sensei of the U.S. Navy Japanese Language School at the University of Colorado, 1942-1946.” Discover Nikkei, April 10, 2008. Online at http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2008/4/10/enduring-communities/

12. For more information, see Military Intelligence Service Association of Northern California. Frequently Asked Questions, 2003. Online at https://www.njahs.org/misnorcal/resources/resources_faq.htm

13. Japanese language has been taught at the University of Oregon since 1940, first by men who also trained members of the U.S. military. In the early 1950s, Japanese language and literature classes alternated every other year with those in Chinese. The Japanese program was almost cut in the early 1970s due to low enrollments.

14. Yoko McClain. “My Personal Journey Across the Pacific.” In Modern Girls on the Go: Gender, Mobility, and Labor, p. 212.

15. McClain, “My Personal Journey Across the Pacific,” p. 226.