by Bryna Goodman, Professor of History and Director of Asian Studies

On September 8, 1922, a mysterious and inexplicable suicide took place in Shanghai’s International Settlement, the Anglo-American-dominated foreign enclave that constituted one territorial authority in a city of multiple and fragmented jurisdictions. A young female secretary who worked at the liberal, politically outspoken Shanghai Chinese newspaper, the Journal of Commerce, was found hanged on the premises. Discovering her missing at an office dinner, a coworker summoned her family members and pushed open the office door, finding her dangling from the cord of an electric teakettle that had been looped around a window frame.

The circumstances of the suicide and the series of events that followed in its wake would, for many Chinese observers and residents of the city, call into question the modernity that Shanghai embodied for China. Since the late nineteenth century, in Chinese novels, in journalism, and in the miscellaneous jottings of intellectuals, semi-colonial Shanghai, for good or ill, represented business and industry, novelty, decadence, Western ideas, fashions, transformations in material life, and new modes of urban organization, management, and political life. In the last decades of the Qing dynasty the foreign settlements of Shanghai sheltered a vibrant Chinese press that swiftly rose to national influence as the medium for the circulation of what was new, dynamic, and—to use a term that captures the uniquely modern combination of novelty and value—newsworthy.

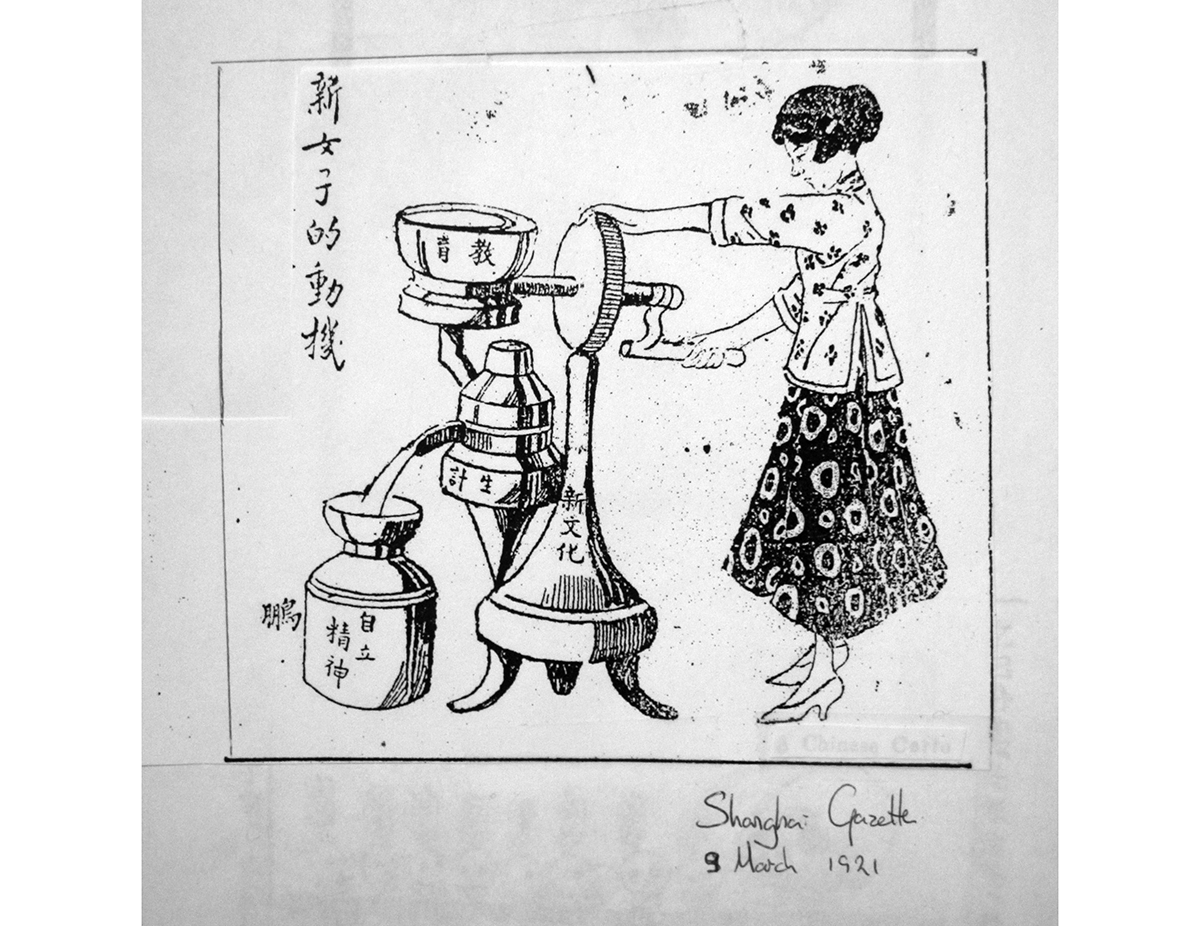

After 1912, when China became a republic at least in name, Shanghai grew as the preeminent center of economic and cultural dynamism. A rapidly proliferating press and a plethora of new urban associations together constituted a growing public realm that circulated ideas and practices associated with republican citizenship. These included ideologies of popular nationalism, democratic participation in governance (particularly for a propertied elite), family reform and gender equality, legal reform, and judicial independence. Shanghai’s flourishing economy and capitalist growth, particularly during the First World War, fueled this public political discussion and social mobilization, funding the press through advertisements and providing capital for the patrons and contributing members of the multitudinous public associations. Politically, however, the new Chinese republic was a disaster, with the new parliament disbanded by a strong-arm government and central control lost increasingly to dispersed regional satraps. But republican notions nonetheless took root, propagated broadly across the country through the new print culture that emanated from the semicolonial conditions of Shanghai’s International Settlement. Establishing themselves within this zone, Chinese newspapers enjoyed some protection from Chinese authorities despite the risks of censorship by the foreign municipal government.

It was these urban developments—the capitalist economy, the social and institutional arrangements of the public realm it materially endowed, and imaginative links between transformed familial and gender relations and the associated construction of a new political order—that seemed to be called into question by the suicide of the young female secretary named Xi Shangzhen, and the subsequent trial and imprisonment of her employer, the influential U.S. educated businessman, political activist, and journalist Tang Jiezhi.

Xi Shangzhen was twenty-four and unmarried when she committed suicide at her workplace. Her nuclear family was poor but she was a member of an influential lineage. The lineage members were prominent in Shanghai financial and journalistic circles. Her family members accused her employer (who many saw as an outspoken political upstart) of two crimes: first, of defrauding Xi of funds on the new Shanghai stock exchange, and second, of pressuring her to be his concubine, and thereby so aggrieving her modern sensibilities that she was provoked to commit suicide. Within months, Tang was tried and sentenced to prison for fraud by a Chinese court. In the course of the trial, a multitude of public associations agitated on both sides of the case. On Tang’s side, business, commercial and native-place associations created a human rights association that protested the corruption of Chinese courts. In the meantime women’s associations agitated for his prosecution and a lengthy prison sentence.

Five years after coming across mention of the case in an obscure journal, while researching another project, I was drawn back to Xi’s suicide when I discovered that it was the subject of a searching essay by the early Chinese Marxist intellectual, Chen Wangdao, translator of Marx’s Communist Manifesto. The moment I looked into newspapers from the period, I encountered many hundreds of articles, essays, cartoons, advertisements and even poems that were dedicated to the case, and I realized the scope of the public scandal that it inspired. In the pronouncements of Xi’s interpreters and contemporary arbiters of Shanghai society, this suicide so “greatly shook public opinion,” that, in the course of the “tremendous social furor” that ensued, “not a pen remained dry.”

This event is at the center of a book I have been working on for the past decade that disentangles the particulars of the case, the factors leading to it, the events set in motion by Xi’s act, and the multiple threads of discussion that followed in their wake. The book takes as its subject the possibilities and limitations of the liberal public culture that was enabled by the economic bubble and the semicolonial framework of China’s early republican era, a public culture that was fueled by an expansive print culture and an associated plethora of new voluntary associations. The case provides a point of entry, as well, into individual lives, male and female, that negotiated the tangle of ideas, networks, institutions, and administrative structures of a place and an era more commonly defined through abstractions: nationalism, imperialism, warlordism, the anti-traditionalism and cultural cosmopolitanism of the New Culture movement, capitalism. For contemporary commentators, the suicide emblematized the contradictory nature of semicolonial governance and the city’s precariousness as an island of imagined modernity within a sea of political fragmentation and military realpolitik. The case glaringly displayed the fragile and contradictory nature of Shanghai’s new economic formations, new cultural aspirations to gender equality, and political aspirations for popular democratic governance, a dynamic public sphere, and legal sovereignty exercised through an independent judiciary.

Bryna Goodman received a 2006 CSWS Faculty Research G rant, and is “very grateful for CSWS support.” CSWS also supported her earlier coedited volume, Gender in Motion: Divisions of Labor and Cultural Change in Late Imperial and Modern China (2005). Goodman currently serves as executive director of the UO Confucius Institute for Global China Studies.