by Stephanie Teves, Assistant Professor, Departments of Ethnic Studies and Women’s and Gender Studies

Acting as a subtle form of resistance to settler colonialism, a film and play about a Hawaiian Kingdom princess who died more than a hundred years ago allows Native Hawaiians to honor Ka‘iulani by thinking about her life and that of the Kingdom critically.

Princess Victoria Kawēkiu Ka‘iulani Kalaninuiahilapalapa Cleghorn died on March 6, 1899, of pneumonia, the apparent result of horseback riding in the rain. Brought on by her previous condition of inflammatory rheumatism, it is often said that she died of a broken heart. Ka‘iulani perished nine months after Hawai‘i was annexed by the United States, six years after the U.S. military backed an illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and eight years after she had been declared heir to the throne of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Since Ka‘iulani’s death in 1899, she has continued to be memorialized in countless productions, including numerous hula, mele, historical biographies, children’s books, plays, and films. Today, there is an elementary school named after her in Honolulu. In 1999 a statue was built of her in Waikīkī. She is honored with an annual keiki hula festival hosted by the Sheraton Princess Ka‘iulani Hotel which was named after her and sits on the site of her former lands. My research focuses on how the love of and focus on Ka‘iulani by Native Hawaiians as well as the general public is indicative of investments people have in particular kinds of narratives about Hawai‘i, settler colonialism, Native sovereignty, and of course, the lives and desires of Native women.

Currently I am analyzing two sites of Ka‘iulani’s modern representation: the 2015 play, “Ka‘iulani” and the 2009 film, Princess Ka‘iulani. Through analysis of the film and play, I consider what our desire for Ka‘iulani signals and how it correlates with contemporary Hawaiian struggles for self-determination. I confront the trope that Ka‘iulani died of a broken heart, considering why the misery contained in Ka‘iulani’s narrative has become so important to Native Hawaiian people today. These performances of the Hawaiian Kingdom challenge settler-colonial efforts to politically domesticate the Kānaka Maoli people, thus allowing performers and audiences to reimagine the future of Hawai‘i and Native Hawaiian self-determination.

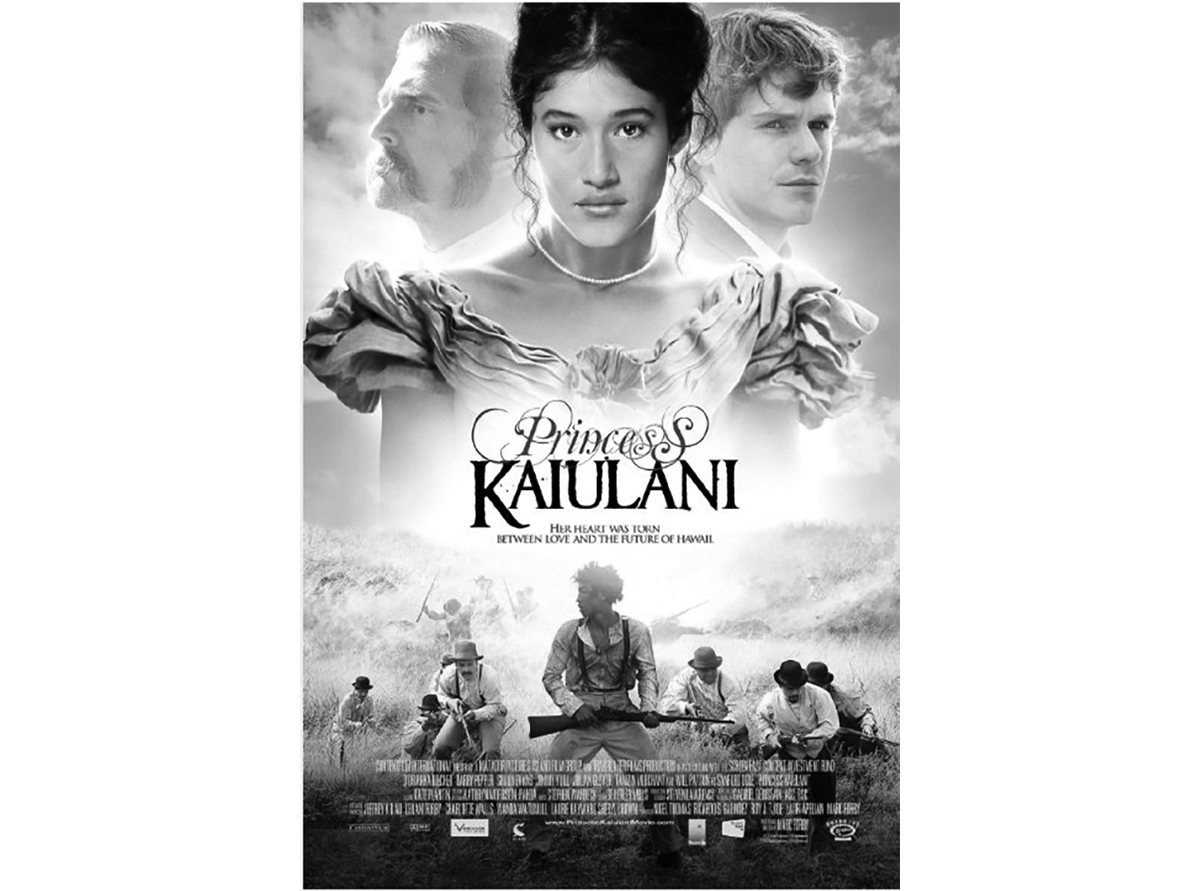

The film, Princess Ka‘iulani (2009) received a moderate amount of critical acclaim, but was widely celebrated within the Hawaiian community as an example of our former greatness. Representations of Hawai‘i and Hawaiians typically invoke touristic imaginaries of the “hula girl” and empty idyllic beach landscapes. There has yet to be a film that visualizes the Hawaiian Kingdom, decked out in Victorian-era opulence with lavish displays of wealth and power. The film documents what most Hollywood portrayals often ignore—Hawaiian resistance to American annexation. For Hawaiian audiences, this counteracts the mass of imagery of Hawai‘i and transports Hawaiian viewers to the late nineteenth century when Hawai‘i was still an independent nation before it was illegally overthrown with the assistance of the U.S. military in 1893.

Dying of a Broken Heart

At the end of the film, the final words on the screen say that many believe Ka‘iulani died of a broken heart. The circulation of this “died of a broken heart” trope signals how Hawai‘i continues to be viewed as an irrational (albeit beautiful) woman incapable of self-rule, thus justifying ongoing U.S. occupation. It positions Hawai‘i as always in the space of the feminine, serving colonialist veiwpoints that figure Ka‘iulani (and Hawai‘i and all “small” island nations) as helpless in the face of colonialism. Portrayed as an inevitable moment of Indigenous independence ceding to Western power, the illegal overthrow is merely a backdrop to a love story between the Princess and her suitor, Clive Davies, who was heir to a plantation fortune in Hawai‘i. Invoked throughout the film and on the film poster, Ka‘iulani was allegedly torn between love and her duty to her country.

I read against this representation of “love” and connect it to what Anne McClintock famously termed the “tender violence” of colonialism.1 The connection—between the heart, the nation, so-called love, and its colonial functions—represents that the tropes of marriage and romantic love between Hawaiian royals and whites accomplished political and cultural work to naturalize the unions between Hawaiian heiresses and white businessmen, whose descendants continue to have power in Hawai‘i.2 Ka‘iulani’s story is represented similarly to the tales of Pocahontas and La Malinche in this sense. In other words, behind the rhetoric of “love” such unions are perceived as the natural submission of Native women to white men and these narratives continue to justify European conquest of Native women and lands. In the case of Ka‘iulani, her relationship with Clive Davies represents the inevitable union or marriage between Hawai‘i and the United States. While this remains the dominant mode of Hawai‘i in the western imagination, in the actual film, Ka‘iulani resists American annexation and never marries any man.

The play “Ka‘iulani,” originally run in 1987 and revived in 2015, similarly represents Ka‘iulani as self-assured and unreliant on patriarchy. Ka‘iulani consistently critiques the pressures exerted on women and Native women especially. What we might today refer to as “Native feminism” is manifested in Ka‘iulani’s analysis of the heteropatriarchal expectations of her and the motivations of the overthrow. Ka‘iulani explains to a ghost figure of her mother, Princess Mariam Likelike, that she feels like a doll, a figurehead trotted out to smile at people. Ka‘iulani knows that she is representative of the Hawaiian Kingdom and the suitors that seek to win her affections want her and her nation as a trophy to “Push me down with your ‘love’ like a stone...you want to use me.” On the issue of marriage, she says, she’d “...die a little more each day.” Correlating marriage with a civil death, Ka‘iulani’s character leverages a disapproval of heteropatriarchy not heard of at the time coming from women. The script thus allows this criticism to come through for a modern audience to ponder the motivations and actions of Ka‘iulani.

The film and the play work to protect, honor, and preserve Hawaiian culture and political claims. These performances function to create cultural memories and remain spaces for dream-work, allowing feelings of misery and resistance simultaneously. Thus, while the settler-state encourages us to focus on our prior cultural life and our political afterlife manifested in various performances, the play and the film form spaces of survival that prioritize and affirm uncontestable Native Hawaiian presence and possibility for the future. The performances relayed the ways that we connect to our ancestors, to each other, and to our histories through memory, witnessing, and physical movement. Within the film and the play, our claims to political primacy are clear and the hegemony of settler-colonialism is interrupted. These forms of resistance function as subtle waves of disruption that redirect the perceived natural union of Hawai‘i and the United States, the path of capitalist “progress,” and ongoing settler-colonialism. These cultural productions are far from perfect, but they allow us to honor Ka‘iulani by thinking about her life and that of the Kingdom critically, affirming the resistance of our ancestors, and of Ka‘iulani herself. This ultimately empowers our memories and allows the Hawaiian future to radiate.

—Stephanie ‘Lani’ Teves is an assistant professor in the Departments of Women’s and Gender Studies and Ethnic Studies. Her book manuscript, “Defiant Indigeneity: Native Hawaiian Performance and the Politics of Aloha,” investigates why Native Hawaiians still perform aloha as “traditional culture” despite its commodification and often detrimental effects. Teves received a 2016-17 CSWS Faculty Research Grant for her continuing work on this manuscript.

Endnotes

1. Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest (New York: Routledge, 1995).

2. Noelani Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua, “Domesticating Hawaiians: Kamehameha Schools and the ‘Tender Violence’ of Marriage,” in Indian Subjects: Hemispheric Perspectives on the History of Indigenous Education, ed. Brian Klopotek and Brenda Childs (Santa Fe, New Mexico: School for Advanced Research Press, 2014), 19.