By Annalee Ring, PhD Candidate, Department of Philosophy

This research project takes up a genealogical method that unearths taken-for-granted assumptions regard-ing contemporary beliefs and practices surrounding cleanliness. Today cleanliness practices are enacted and are treated as “normal” without considering how they have been shaped by vectors of contingent influences including social and political institutions, technological developments, global politics, and power discrepancies. Further, we surveil and discipline ourselves and one another to enact cleanliness practices that have been normalized. This project seeks to denaturalize our concept of cleanliness and our cleanliness practices through tracing these contingent vectors in which they emerged, showing both the historical accidents and sociogenic continuities that led to our contemporary assumptions about cleanliness and the practices that we take for granted.1

Through this methodology, this project unveiled a myth that emerged in the 19th century that promoted white supremacist practices and settler colonialism: whiteness as cleanliness and blackness or brownness as dirtiness. This myth of whiteness as cleanliness supported white supremacist and settler colonial institutions and practices, which in turn naturalized this myth. The myth of whiteness as cleanliness had the historical motivation of supporting white supremacy, settler colonialism, patriarchy, and classism. This myth is historically and sociogenically constructed but naturalizes the associations between whiteness and cleanliness as well as blackness and brownness with dirtiness, women with dirtiness, and people experiencing poverty with dirtiness. Importantly, our contemporary cleanliness practices emerged during the 19th century as this mythologization of whiteness as cleanliness developed—as such, this mythology has influenced our contemporary cleanliness practices.

Our contemporary cleanliness practices emerged rather recently. At the beginning of the 19th century, most Euro-Americans would bathe three times: after their birth, before their marriage (only required if they were categorized as a woman), and after their death.2 Laundry was typically done once a year, as was cleaning surfaces in one’s home, known as the annual spring cleaning.3 Handwashing was largely nonexistent. These practices were by no means universal; Indigenous peoples found Euro-American colonists to be dirty and smelly.4 Members of the Wampanoag tribe attempted to teach colonists to bathe, but to no avail.5 Victorian-era practices and beliefs surrounding modesty presented an obstacle to bathing for Euro-Americans who were uncomfortable with their own nakedness.6

However, throughout the 19th century, Euro-American practices transformed drastically and contemporary cleanliness practices emerged in the late 19th century.7 Frequent bathing, laundering, surface sanitizing, and handwashing emerged as appearing clean became an important sign of social status. This project in its full form considers several vectors that contributed to this emergence, but I will detail two here: the institution of chattel slavery and the institution of Indigenous boarding schools.

First, during the 19th century, the practice of slavery was scrutinized and abolitionist ideology gained traction. Abolitionist ideology represented a threat to “the Southern way of life,” and pro-slavery ideology proliferated, responding with public health.8, 9 Justifications for the practice of slavery claimed that it was not just a political, economic, and social system, it was also considered a “curative and preventative” hygienic system.10, 11 Justifications for the hygienic system included attempts to establish the sanitation police, who would have the power to order inspections and purifications, to have jurisdiction over hygienic asylums and hospitals, to legislate for “the conservation and progress of the race” in order to “prevent degeneration by prohibiting intermarriages manifestly and perniciously degenerative.”12 The movement considering the institution of slavery as a hygienic system of public health not only contributed to pro-slavery ideology but also justified the surveillance and enforcement of hygiene and eugenic practices through policing.

Additionally, sociologists defended slavery through claiming that enslavers were like father figures to the enslaved, who were likened to children who could not take care of themselves.13 This literature defended the institution of slavery while it was under moral scrutiny because the enslaved would supposedly be taught the virtue of cleanliness; allegedly enslavers would ensure the adoption of cleanliness practices in the enslaved, which, it was claimed, they could or would not do on their own.14 However, Booker T. Washington’s autobiography Up From Slavery demonstrates that this defense of slavery is made in bad faith as many enslavers did not allow people who were enslaved to bathe—in fact, this was one way enslavers maintained a hierarchical relationship between enslavers and the enslaved, further perpetuating the association between whiteness and cleanliness.15

The second institution that contributed to our beliefs and practices surrounding cleanliness are Indigenous boarding schools, which served as one of the institutions that enacted the settler colonial agenda. Indigenous removal and relocation were supported through descriptions of Indigenous peoples as dirty. State-sanctioned ethnic cleansing was written into legislation—including monetary rewards for scalps of Indigenous peoples, conditions for statehood requiring more settlers than Indigenous peoples, and biological warfare to weaken resistance to settler colonist violence.16, 17 Describing Indigenous peoples as vermin was common and developed associations of disease and dirt.18 This language was also used in boarding schools’ curricula.19 The 1885 Superintendent of Indian Schools describes their first day of school: “Strip from the unwashed person of the Indian boy the unwashed blanket, and, after instructing him in what to him are the mysteries of personal cleanliness, clothe him with the clean garments of civilized men.”20

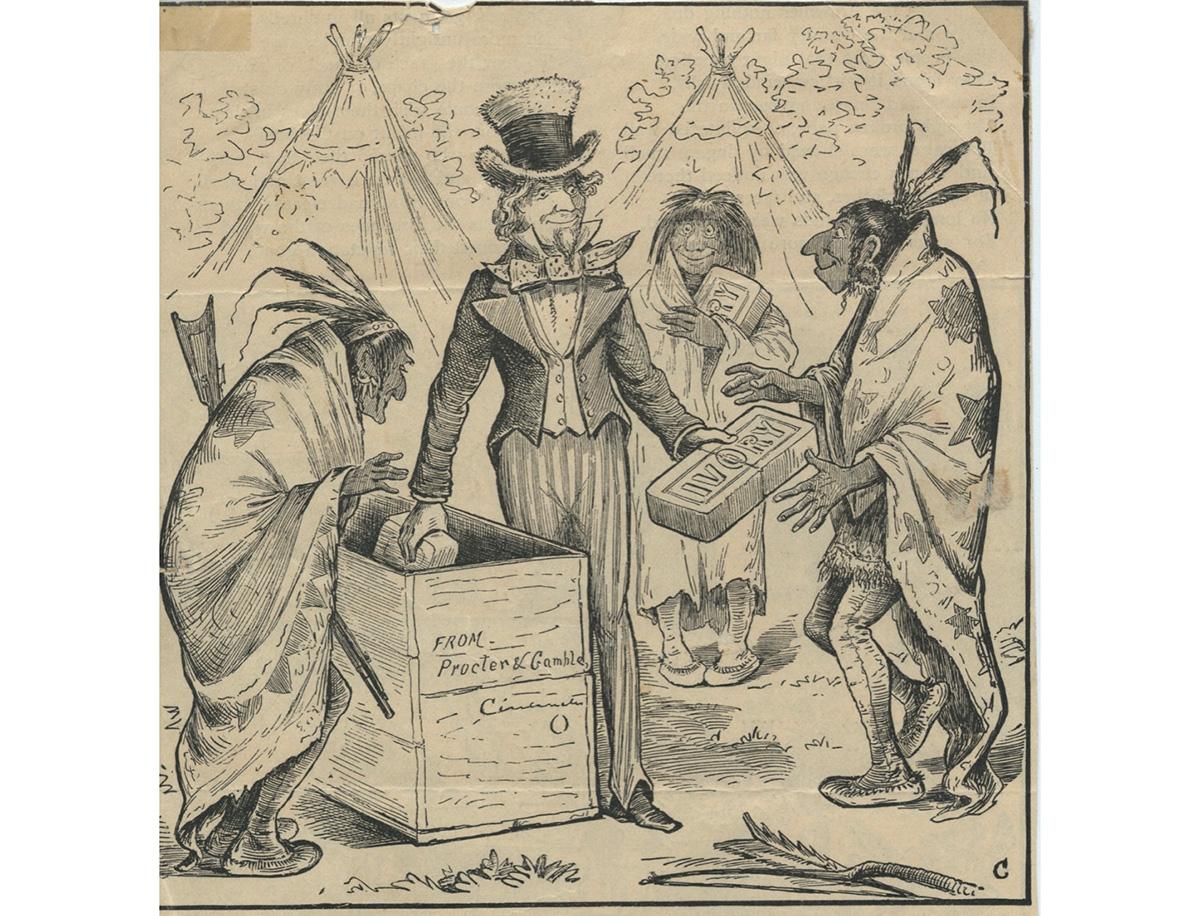

This idea of cleanliness as a feature of white civilization was popularized through soap advertisements.21 Advertisements framed settler colonialism as a paternalistic sharing of civilization, of soap, spreading the myth that colonization is as benign as washing or cleaning.22 Some soap companies, like Unilever, made the equation between soap and civilization even more explicit as their company slogan was “Soap is civilization.” Soap advertisements claimed that teaching the virtues of cleanliness was the “white man’s burden.”23

As such, my research argues that our contemporary beliefs and practices surrounding cleanliness have been influenced by white supremacist and settler colonial institutions, including the institution of slavery and the institution of Indigenous boarding schools. More of my research can be found in the APA Women in Philosophy blog.

—Annalee Ring received a 2021–22 Graduate Research Grant from CSWS.

References

1 Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, 1st Evergreen ed. (New York: Grove Press, 1991).

2 W. Peter Ward, The Clean Body: A Modern History (Montreal: Montreal, 2019).

3 Ward.

4 Feenie Ziner, Squanto, Reprint. Originally published: Dark Pilgrim. Philadeplhia: Chilton Books, 1965 (Hamden, Connecticut: Linnet Books, 1988).

5 Ziner.

6 Ward, The Clean Body: A Modern History.

7 Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest (New York: Routledge, 1995).

8 Carl A. Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States (New York: New York University Press, 2015).

9 Carol (Carol Elaine) Anderson, White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide (New York: Bloomsbury USA, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2016).

10 Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States, 38.

11 Henry Hughes, Treatise on Sociology, Theoretical and Practical, xxxviii, 45-292p. (Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1854), http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008676465, 284.

12 Hughes, 66–67.

13 Saidiya V. Hartman, Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

14 Zimring, Clean and White: A History of Environmental Racism in the United States.

15 Booker T. Washington, Up from Slavery (Open Road Media, 2016), 25.

16 Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015).

17 As Grenier’s work details, conversations about Indigenous peoples included descriptions of them as vermin: “Could it not be contrived to send the Small Pox among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians?” “Inoculate the bastards with some blankets that may fall in their hands…effectually extirpate or remove that vermin.” See: John Grenier, The First Way of War: American War Making on the Frontier, 1607-1814 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 144–145.

18 Further this demonstrates that animals considered to be vermin could be removed without moral consideration, a sign of human supremacy in addition to white supremacy.

19 US government’s campaign “Kill the Indian, Save the Man” would “civilize” Indigenous peoples through assimilation and education. This framed settler colonialism as a “coincidence of interest” as Jefferson phrased it, as Indigenous peoples had an abundance of land but lacked civilization whereas white people were “civilized” but lacked land. Education was deemed to be the solution; it was framed as a paternalistic sharing of civilization rather than a violent insurance of white supremacy through the elimination of millions of peoples and dozens of cultures. As such, the reframing of settler colonialist practices as paternalistic sharing of civilization placed less moral scrutiny on the practice.

20 David Wallace Adams, Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928, (Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas, 1995), 30–31.

21 Rahima Schwenkbeck, “Keeping Consumers Clean: Ivory Soap,” in We Are What We Sell: How Advertising Shapes American Life... and Always Has, vol. 1, 3 vols. (Oxford: Praeger, 2014), 197–212.

22 McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest.

23 Pear’s Soap, “The First Step toward Lightening the White Man’s Burden Is through Teaching the Virtues of Cleanliness” (Cosmopolitan, v. 27, October 1899), http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b32850.