by Alia Yasen is a PhD candidate in the Department of Human Physiology

Scientists have known for some time that the female brain reacts differently to a mild traumatic brain injury, or concussion, than a male brain. Women tend to suffer more severe outcomes after concussion, including a higher number of post-injury symptoms, slower reaction times, and more significant declines in cognitive function. Despite this information, concussion management and recovery protocols tend to follow a one-size-fits-all approach and manage men and woman similarly. This approach is problematic, as these management programs are based on evidence almost entirely from men. Continually overlooking women leaves other vulnerable groups with a higher incidence of concussion, such as elderly women, women in prisons, and survivors of domestic violence, to become ignored as well.

For most people, symptoms tend to recover within two weeks of sustaining a concussion. However, 10-15 percent of people who have sustained at least one concussion in their life will continue to experience symptoms chronically. An estimated 5.3 million Americans currently live with a concussion-related disability, and for some, the effects of just a single concussion may be permanent. For my research study, I wanted to learn about what factors were responsible for predicting concussion risk and recovery outcomes. I chose to investigate factors such as biological sex, concussion history, and genetic predictors.

My research focuses on recovery of function in the motor cortex, or, the part of the brain that controls movement, after concussion. I investigated four different groups of men and women, including a) those who had never been diagnosed with a concussion, b) those who had sustained a concussion in the past, but had fully recovered, c) individuals who had recently sustained a concussion (within 72 hours), and d) individuals who still experienced chronic symptoms from a concussion sustained at least a year ago.

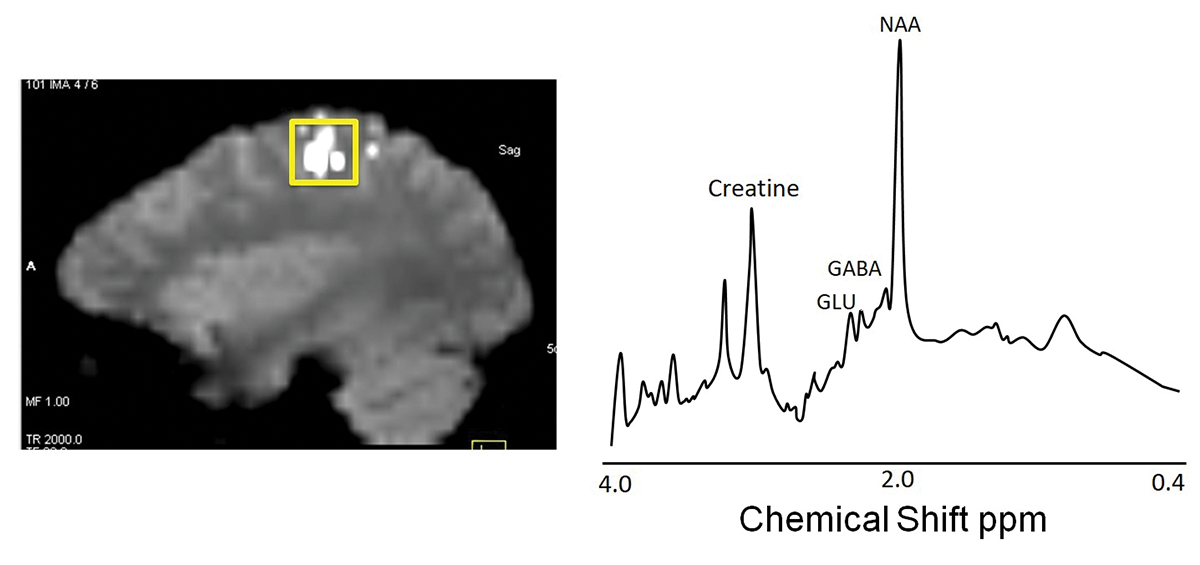

I used a technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to test how effectively the brain communicated with the muscles. To do this, I placed a sensor on one of the hand muscles and recorded the muscle activity after magnetically stimulating the brain with the TMS machine. This process is a painless way to non-invasively measure how the motor cortex functions.

I also used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to locate the motor cortex in my participants and directly measure the chemicals in that specific part of their brain. I was interested in looking at the chemicals involved with exciting and inhibiting the nervous system.

Research suggests that genetic factors may play a part in predicting how well a person recovers after a concussion. I analyzed saliva samples from my participants to determine if they possessed a version of a gene that predicts concussion outcomes.

Recruitment for this study is still ongoing, but so far I have reported a trend for women to display lower levels of inhibition in the motor cortex compared to men, regardless of whether they had experienced a concussion or not. Even though women display lower levels of inhibition in the brain, the amounts of excitatory and inhibitory chemicals in the brain appear to be similar between women and men. I was surprised to find no differences in brain function or amounts of chemicals in the brain between the four concussion groups. Results from the genetic data show that 50 percent of participants in the concussion group with chronic symptoms had the version of the gene that is associated with poor outcomes following concussion. To put this into context, only 14 percent of the general population in the United States is reported to have this version of the gene.

Further study is still needed at this point to fully understand the role of motor cortex function and genetic risk factors in concussion recovery, but I am excited to continue exploring this topic. Establishing physiological evidence for differences in concussion recovery in men and women will hopefully, one day, be used to help establish more effective, sex-specific rehabilitation protocols after brain injury.

—Alia Yasen, a PhD candidate and graduate teaching fellow in the UO Department of Human Physiology, received a 2017-18 CSWS Graduate Student Research Grant in support of her project “Physiological Consequences of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Women and Men.”