by Helen Yi-lun Huang, Graduate Student, Department of English

“Yes, we have no bananas

We have-a no bananas today.”

A famous hit in 1923— “Yes! We Have No Bananas”— described how a grocery store owner explained the shortage of bananas. The owner would provide everything customers asked except bananas. The syntax of the repeated sentence, “Yes! We Have No Bananas,” seems quite odd to listeners: how could an owner affirm the shortage situation first but tell customers that no bananas were available later. How could affirmation and negation coexist in the same sentence? How could this song become a hit in the ’20s and why do we often hear people humming it?

Actually this song is the epitome of the production chain of bananas in the United States in the early twentieth century. It not only reveals how the U.S. retail market heavily relies on the banana supply from Central American and the Caribbean but also demonstrates how advertisement tactics promote bananas in the 1920s.

The first banana plant was introduced to Santo Domingo in 1516, and, spreading extremely quickly, by the seventeenth century, the banana had become a popular subsistence crop of tropical Americas. Some bananas were transported by the ships travelling from the Caribbean to North America (Davies, 24). For the American people of the colonial period, the banana acted as an odd and exotic fruit. In the 1870s and 1880s, bananas were a high-end luxury and only could be found on hotel and holiday menus as well as for special occasions in fall and winter seasons. In the 1890s, as the United Fruit Company built up a railroad system in Central America, steamship lines operating between the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, and refrigeration railcars in the United States, bananas were transformed from a perishable fruit to a year-round and inexpensive commodity sold everywhere in America. The business of the banana trade became more prosperous, and the demand for bananas in the States increased. At the end of the nineteenth century, the banana business in the Americas conducted by the United Fruit Company became a monopoly, not only dominating the way in which bananas were traded in the States, but also systematically exploiting the natural resources of Central America to facilitate U.S. trade advantages and demand.

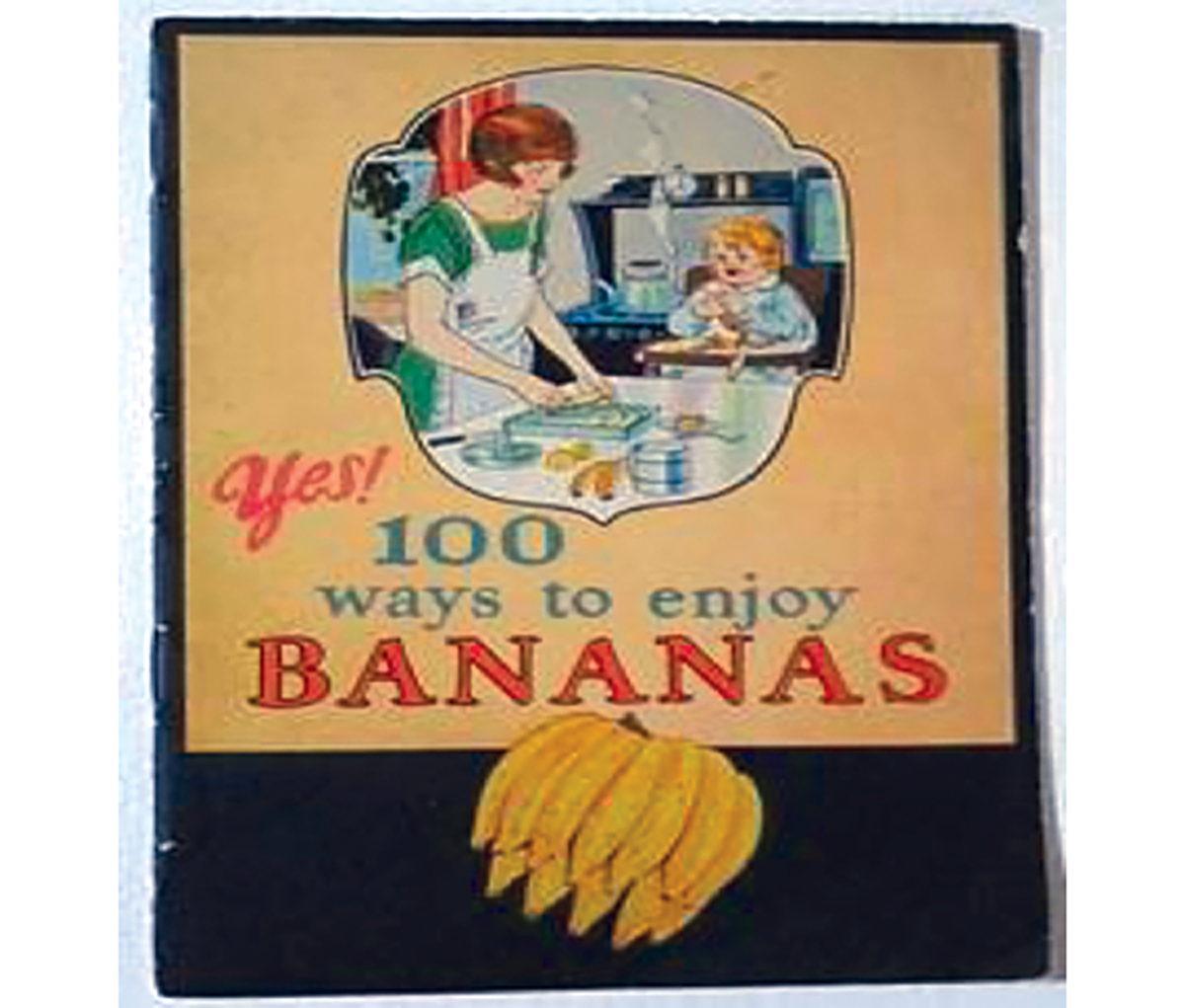

If bananas became one of the popular fruits in American grocery stores at the end of the nineteenth century, the coming question would be how to promote bananas to American consumers. Cookbooks carrying knowledge of germ discoveries, home economics, new methods of cooking soon acted as an ideal vehicle to market bananas to American families. The commercial strategies to promote the banana via cookbooks reinforced how women were coupled with the banana consumption and preparation. The cookbook cover of Yes! 100 Ways to Enjoy Bananas (1925) portrayed a kitchen scenario in which a housewife cut the banana while her baby sat on a high chair while eating his yellow fruit. This representation located the woman as the role of a meal provider, responsible for taking care of her child’s health and nutrition. In addition, the cookbook cover was designed to teach readers how to enjoy bananas. In a clean and well-lighted kitchen, a housewife easily cuts bananas into pieces and puts them into a box. Meanwhile, the child, sitting next to his mother, happily eats a peeled banana. In this cover picture, white creates a sense of cleanliness and mother’s green dress and yellowish bananas add vitality to this daily scenario, which symbolizes eating and preparing bananas as an enjoyable and delightful experience. The implied message, I contend, endows women with two identities: modern housewife and consumer. Through reading cookbooks, the twentieth-century women acquired new cooking knowledge, fulfilling the traditional expectation of being a dream housewife to manage her family. Different from the nineteenth-century cookbooks focusing on heavy protein dishes, this book cover demonstrates a new image that a housewife is able to transform a light snack like bananas into nutritious food for her kid. This fruit preparation looks simple and easy but it satisfies the appetite of her child as well as resonates with the role a housewife plays. The modern housewife is not a slave in the kitchen for endless cooking but gracefully and leisurely feeds the whole family. Moreover, the title “Yes! 100 Ways to Enjoy Bananas” simultaneously encourages the housewife readers to act as consumers to purchase more bananas for their families. The word “Yes!” with an exclamation mark cajoles female readers or housewives into buying bananas for daily food and believing bananas to be a great purchase. Also, the exclamation of “Yes” could be reference to the hit “Yes! We Have No Bananas.” Through refreshing the readers’ hearing and sensational attachment to this hit, the publisher brought back the readers’ memory on bananas and channeled their nostalgic emotions to the affirmative language act: Yes! Bananas! Moreover, 100 Ways to Enjoy Bananas advocates how the preparation of bananas can be various and how the taste can be scrumptious. The visual attraction of “Yes” and “Bananas” colored with red coaxes the readers to respond to the implied marketing message: buying more bananas. In other words, the pairing of the kitchen scene and the affirmative book title serves as a linchpin to construct female identities as homemaker and consumer.

—Helen Huang received a 2016-17 CSWS Graduate Student Research Grant in support of this research project.

Works Cited

1. Cantor, Eddie. “Yes! We Have No Bananas.” Frank Silver and Irving Cohn. 1922.

2. Davies, Peter N. Fyffes and the Banana: Musa Sapientum: A Century History 1888-1988. London: The Athlone P, 1990. Print.

3. Yes! 100 Ways to Enjoy Bananas. New Orleans: Bauerlein Inc, 1925. Print.