by Anita Weiss, Professor, Department of International Studies

Violent extremism has manifest in myriad ways over the past two decades in Pakistan, and local people in Pakistan are left questioning the causes behind it. This violence often emerges from religious extremism, which both causes and reflects cataclysmic chasms between different constituencies, destroying social cohesion in its wake. In response, while the Pakistan state and military have sought to counter this extremism through different strategies, I argue in this research project that it is the myriad ways that local people in Pakistan are responding to lessen the violence and recapture indigenous cultural identity that promises more effective long-term outcomes. They are engaging in various kinds of social negotiations and actions whether by creating NGOs like Karachi’s The Second Floor (T2F) that provides a venue for local people to have a voice, the rejuvenation of indigenous forms of music such as playing the rubab, promoting long-term incentives to encourage participation and self-reliance by the Orangi Pilot Project, or the cultural values and peace studies curriculum championed by the Bacha Khan Education Foundation schools in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

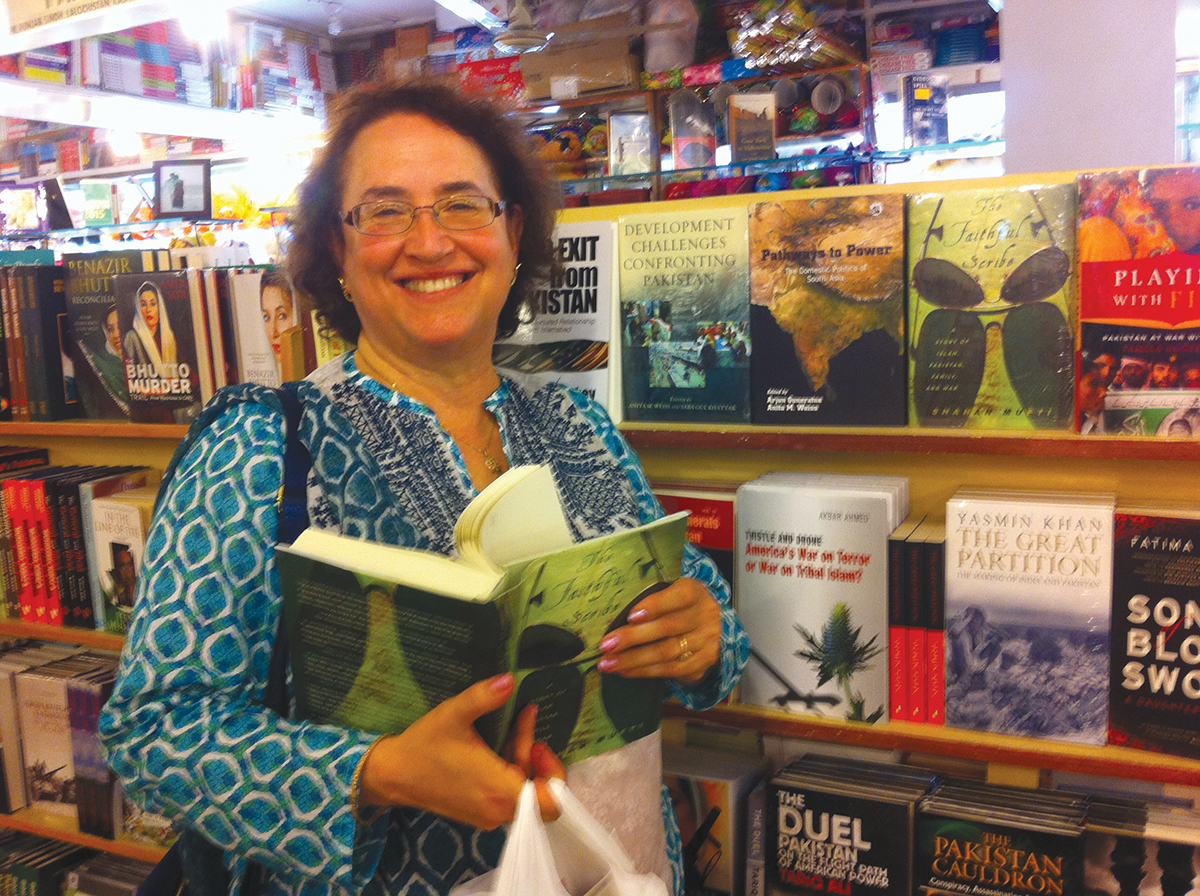

I began brainstorming with scholars, practitioners, policymakers, and others about my ideas for this research while in Islamabad during the summer of 2015, and began conducting interviews at schools and with poets in Swat with then incoming graduate student, Aneela Adnan, in August 2016. During my Research Leave in Winter 2017 (January-March), I began my fieldwork in earnest in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Mardan, Charsadda and Peshawar) and in Karachi. I will be returning to Pakistan in late September 2017 – mid-March 2018 on a Harry Frank Guggenheim Research Award to conduct field research throughout Punjab (beginning in Lahore, then venturing out to Sargodha, Jhang, Faisalabad, Multan, Dera Ghazi Khan, and elsewhere) and then in Upper Sindh. I intend to use the final month in Pakistan to return to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to see an initiative undertaken by Khwendo Kor, a women’s NGO based in Peshawar, to rebuild social relations in a village near Nowshera from the ground up to promote gender, class and sectarian equity, and visit other areas. I also hope to visit Baluchistan, if possible, as well.

I met Hasina Gul, who uses poetry as a way to counter violent extremism, in Mardan in January. She has broken social barriers as this is a domain, especially in Pakhtun society, dominated by men. She sees herself as a symbol of resistance today. When she began writing poetry, it was about love and romance but that was short-lived. As tragic events unfurled in her area, the inspiration for her poetry became war and conflict; the attacks on the Army Public School (APS) in Peshawar in December 2014, and the later terrorist attack at Bacha Khan University in Charsadda in January 2016 motivated her further to speak out. She also draws inspiration for her poetry from the oppression women face in her society, and how they are not given a decision-making role in their lives.

Her poetry expresses powerful cultural sentiments, the kinds that have long mobilized Pakhtuns into solidarity with one another:

I will not tolerate any wrongful power, I cannot call something that is wrong, right.

But when I look around me, all these oppressive walls, all these suppressive shackles,

my lips are sealed and they have deafened my ears.

The oppressive society’s eyes bore into me and they swipe at my neck with their claws,

trying to silence me, so that no one may find out about my plight.

They want me to listen to them and obey them, but never complain or question.

I wish I could gouge their [oppressive society’s] eyes out and break their suppressing

claws. But to no avail, they keep coming for me, tormenting me.

They bind my hands and my feet, and they justify it by telling me where I’ll go and to

whom I’ll go.

I look around me, and there’s no one I can turn to.

I haven’t a home so I bow my head and poison myself, because I refuse to call what is

wrong, right.

Sometimes I resist, sometimes I bite my tongue.

Another poem speaks to her frustration of not seeing an end in sight to the violence that is decimating life around her:

Murderers! Tyrants! Enough! This land has turned scarlet with all the innocent blood

that you have spilled.

Eyes have run out of tears to cry at the cemeteries.

Form a jirga [community council] to bring love to everyone.

Peshawar will be young again.

Ninglahar [a village in KP] will have spring again. Kabul will smile again.

Even death is appalled by what you have done.

Death was something to look forward to when the time was right, but you take people

away before their time.

We would look forward to being on our deathbeds and being surrounded by loved ones

who would give us a peaceful send-off.

People would go to schools; they would live in harmony and unity, and strangers were

treated with utmost respect.

I would have been content that I lived a long, happy life.

But murderers, tyrants! You have showered us with bullets of hate and sorrow. Please

listen to me for a bit; please rest your arms for a lot of blood has been spilt.

She sees her poetry affecting her audiences’ thoughts and actions. She recounts that people have come up to her after a mushaira (poetry recitation) and said “We don’t want to engage in war, we want to educate our children, and we want to empower our women. We want to be able to bring about progress.” But the rampant terrorism occurring around her is impeding the efforts people are taking to progress. After the APS attack, she went to Swat to recite her poetry and said that the people in the audience were crying because they were overcome with emotion:

“They said that we are peace-loving too, and they have had it with war and conflict. They said we don’t just want this for Swat, but we want this for the whole world. Ultimately, we want to do away with the concept of war altogether. A great number of people are upset these days, and this was their reaction. These people have to die for a war they didn’t start . . . The casualties of war aren’t just our lives, it’s also our dignity, our children. We are right in the storm’s eye, the center of war. We are the ones who are made to fight; we are the ones who perish. Yet they are the ones who win the war. It is their fate to win, as it is ours to lose.

“Pakhtuns are very innocent, trusting people. If someone speaks to them nicely, they are willing to give them anything, even their guns. This is why we fight their wars. This is the problem we face.”

Pakistan recently bestowed upon her its highest civilian award—the Tamgha Imtiaz—on Republic Day, 23 March 2017, in recognition of her poetry. But while the Pakistan government recognizes her efforts, she doesn’t think they will do anything else to cultivate awareness and spread the message she is trying to make among the masses. Through her poetry, she hopes that the feelings she is able to evoke will help people to spread this message among their community. Another poem captures this sentiment:

If a house could be built like this, the dream that you have seen I have seen as well. But

alas, our current circumstances have taken our dreams away from us.

But I still dream of that house where I will live with you, where all our desires will be

fulfilled. Full of love, I shall wear clothes and jewelry of flowers.

Our whole community will break into song, and peace shall prevail everywhere.

We shall help solve one another’s problems together and the face of hatred will be

destroyed.

Everyone shall dance and engage in merrymaking at local carnivals.

It will be the season of adorning yourself in henna, dupattas and chadors.

It is the dream of Bacha Khan, it is the vision of Samad Khan, it is Greater Afghanistan.

—Anita M. Weiss is a professor in the UO Department of International Studies and participating faculty in Asian Studies, PPPM, Religious Studies, and Sociology.

End Notes

When Anita Weiss met with Hasina Gul in Mardan in January 2017, Gul recited her poems from hand-written notes, and for some that had been published, she revised as she recited. All of her poetry was translated from Pashto either by Zenab Adnan or Aneela Adnan, with permissions given to Anita Weiss to reproduce these poems in her research publications by Hasina Gul as well as by her translators.