by Carol Stabile, Director, Center for the Study of Women in Society, Professor, School of Journalism and Communication and the Department of Women’s and Gender Studies

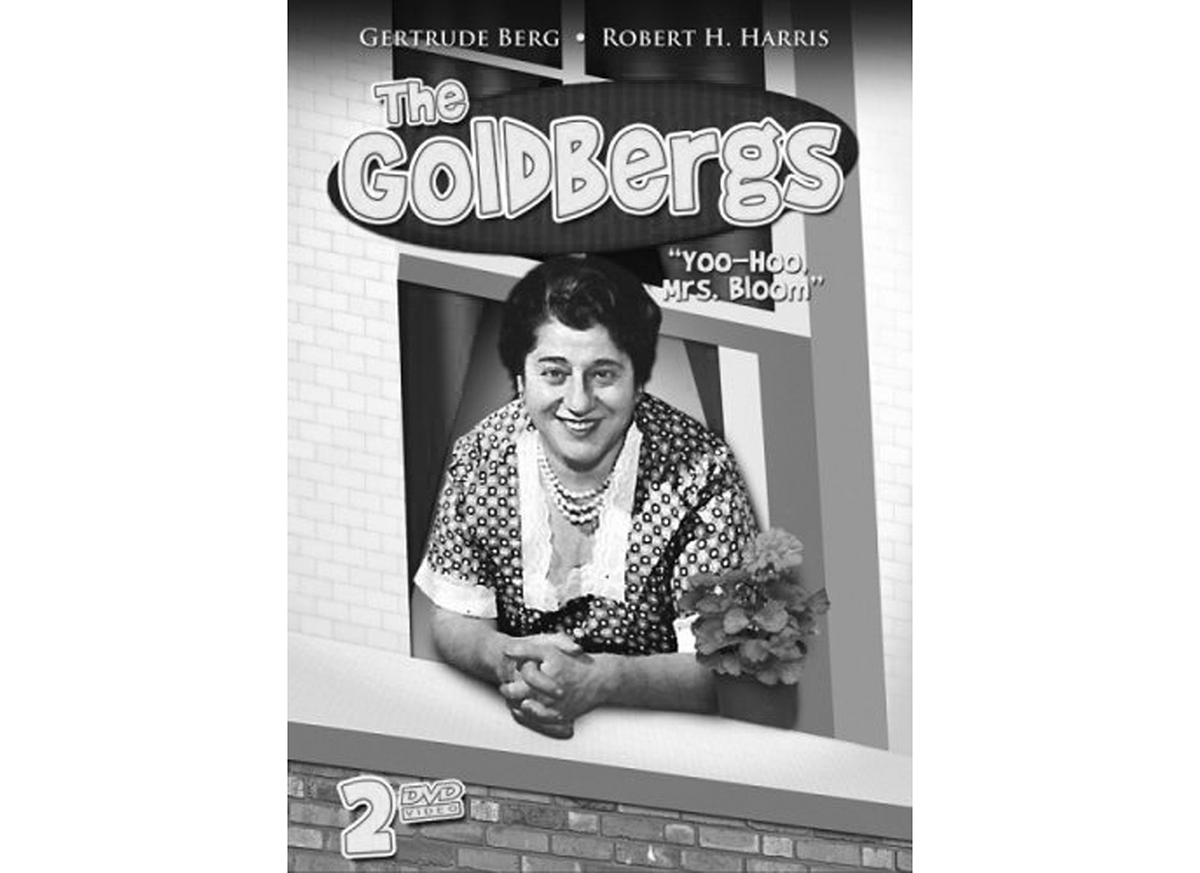

IN 1950, GERTRUDE BERG HAD IT ALL. Married to Lewis Berg for twenty-two years, mother of two grown children, owner of a luxurious ten-room duplex on Central Park West and an estate in upstate New York, Berg was a highly successful producer, director, writer, and actor in broadcasting, who had parlayed the popularity of her signature production, The Goldbergs, into a multimedia success story that included books, Broadway plays, comic strips, a clothing line, and a Hollywood film.

As it turned out, the only thing that could defeat The Goldbergs was the broadcast blacklist. Over the past decade, I’ve been researching a book on women writers who were blacklisted in broadcasting in 1950 because of their political views. In the main, the blacklist succeeded because anti-communists were able to argue that audiences despised these dangerously un-American ideas about fighting Jim Crow, advocating for world peace, and respecting religious and political viewpoints that diverged from those of white, conservative Christians. But anti-communists’ representations of American audiences were rooted largely in conjecture and the kinds of metrics, surveys, and other devices invented by the industry itself to represent and sell these audiences to sponsors and advertisers. The industry and anti-communist representations of audiences didn’t always match up with what audiences themselves were saying, as documented in the letters fans wrote to stars, networks, advertisers, and sponsors either endorsing or excoriating particular programs. There’s a great deal of interest in the field of media studies right now about fans and new media that’s understood to be more interactive than “old” or “traditional” media. But archival evidence of fan activity reveals an American audience at once more progressive, diverse, and engaged than the anti-communist view of the audience has led us to believe. Gertrude Berg is a case in point.

Berg’s story begins well before 1950. The Rise of the Goldbergs first aired in 1929. The series revolved around the everyday lives of the Goldbergs, an immigrant family who lived in a tenement in the Bronx, where Molly and husband Jake struggled to make ends meet. Like Berg’s own grandmother, Molly was an immigrant who tried to balance assimilation with the Jewish culture and traditions she brought with her from Eastern Europe. In crafting the series, and like many “minority” producers, Berg was acutely aware that she was fighting a tradition of representations she understood to be “demeaning and exploitative.” In opposition to these images, Berg wanted to show what the “aspirations of Jewish immigrants were.”

Neighbors who lived in the Goldbergs’ tenement struggled with real-world problems and not manufactured crises about consumer choices. The Mrs. Bloom to whom Molly continually yoo-hoos through her trademark window and dumbwaiter never seems to have enough food for herself and her children. Molly shares food with the Blooms and eventually cajoles Jake into hiring the unemployed Mr. Bloom. Molly even takes on the Protestant work ethic. In one episode, Jake lectures Molly on the importance of ambition, telling her in exasperation, “I can see you’re only a voman. And don’t understand life. Vat wod you know about a man’s ambitions?” But Molly still doesn’t understand men’s ambitions and in frustration, Jake tells her:

Look, I’ll give you a far instance . . . . Ef a man is got five dollars, he vants ten dollars! Get de point? Mr. Finkelstein started with ten machines in his factory, and he didn’t stop embitioning ontil he got fifty.

Thoughtfully, Molly looked at him. “And dat’s vat you call membition? Oy, Jake, by me dot looks like a sickness.”

Molly’s commitment to family and community drives her resistance to Jake’s attempts to move the family to a larger and more lavish apartment in a more desirable neighborhood. Until the blacklist jeopardized the future of the series, Molly resolutely found ingenious excuses for staying in their tenement in the Bronx.

Berg’s radio family resembled her real family in its commitment to diversity. Berg, her daughter later recalled, lived in “a very bohemian, eclectic atmosphere. Jews, non-Jews, Blacks, Whites, gays, non-gays—all kinds of people were in and out of our home.” Later, Berg reflected that, “I didn’t set out to make a contribution to interracial understanding. I only tried to depict the life of a family in a background that I knew best.” In so doing, for a generation of radio listeners, Molly Goldberg came to symbolize a form of American motherhood that embraced pluralism, tolerance, and respect—all those characteristics that anti-communist mothers like “super-patriot” and Mother’s Movement leader Elizabeth Dilling identified as evidence of un-American activity.

Berg’s most important contribution to broadcasting thus may have been the way in which she celebrated Jewish life and culture, in the context of a working-class, immigrant family who loved and celebrated America and who staked a claim to being a specifically American family. To do this at a time when support and sympathy for anti-immigration and Nazism were peaking in the United States, when the language of Americanism was being successfully deployed by white supremacists like the Ku Klux Klan and anti-communists like Elizabeth Dilling and J. Edgar Hoover, when the radio waves were dominated by the fascist provocations of Father Charles Coughlin, attests to the power Berg had in the industry. And, contrary to the logic of anti-communists, listeners recognized and appreciated The Goldbergs because of its commitment to progressive values and ideas.

Judging from its multiple cancellations, near constant search for sponsors, and rotating time slots, The Goldbergs was never a hit among networks, advertisers, and sponsors. Like other programming of the time, The Goldbergs was at the mercy of the thirteen-week or cancellation clause written into contracts, which stipulated that at the end of every thirteen-week period, a program could be cancelled, no matter what other provisions the contract contained. In addition to the thirteen-week clause, sponsors seemed to be constantly on the lookout for reasons to cancel the series. The Goldbergs was cancelled for the first time by NBC in 1934. This first cancellation was caused, Berg said, because sponsor Pepsodent had offered premiums to listeners who wrote in, and the company was unable to meet the demand. Berg biographer Glenn D. Smith argues that the cancellation was more political and owed to Berg’s demands for better compensation for herself and her cast and greater executive and creative control. Despite the series’ evident popularity among listeners, when it finally returned to the air in 1936, it switched network affiliations five times before being cancelled again in 1945.

In contrast to industry attitudes toward The Goldbergs, fans of the show told a very different story about what they wanted, writing thousands of letters expressing their enthusiasm for it. In 1929, for example, Berg “came down with laryngitis and the show was taken off the air for a week.” As an unsponsored program, The Goldbergs had been moved around time slots to fill in dead spaces. “With that kind of schedule,” Berg observed, “it’s hard to build an audience.” Both Berg and NBC were surprised when the network received some 18,000 letters from fans asking what had happened to Molly Goldberg. For a local program, that kind of “mail response was considered phenomenal.” During the 1930s, the program had close to five million listeners, according to Berg, and the network received thousands of fan letters a week.

Mary E. Kelly of Cleveland, Ohio wrote:

We love Mollie!—For her tolerance, which she preaches so beautifully—without preaching; for her understanding heart; for her love of her little family; for the many worries she hides so valiantly behind her happy ways; for her patience in achieving the desired end in view, without hurt or unkind speech;—for her sympathy with the views of the younger generation in her family, without relinquishing her gentle authority—in fact, for just being Mollie.

Fans also praised The Goldbergs’ messages of acceptance. Other listeners volunteered information about their own ethnicity and religion. One letter from Mrs. John A. Russell, addressed to “Dear Goldberg People,” stated: “Tho we are Gentiles, we have in New York some very, very dear Jewish friends, and, in fact, had the little girl of the family in our home for five years, while her mother was ill. So I can appreciate ‘Molly’s’ maternal feelings, so wonderfully expressed.” The editor of the Catholic Standard wrote Berg to say that her program made him a better Christian, while the nuns of one Catholic sisterhood, who had given up The Goldbergs for Lent, famously requested copies of the scripts to read later so they would be able to follow subsequent episodes.

Letters from non-Jewish listeners and viewers repeatedly direct attention to the series’ role in fighting domestic anti-Semitism. As late as 1949, a television viewer wrote:

You are doing a masterly job toward fighting anti-Semitism. I am not Jewish, but I have many cherished Jewish friends, and really the whole problem is getting acquainted, isn’t it? That is one reason why your program is so important. I especially enjoyed tonight’s program about the Seder. The humorous part was delightful, but I am so glad that you finished the program with the very beautiful ceremony that belongs with the spirit of the Seder.

For Jewish listeners and viewers, The Goldbergs’ presence on radio and television had a deeply personal and urgent meaning. Commenting on a 1933 Seder broadcast, a listener from Queens wrote:

I believe the Jews throughout the world owe to you and your sponsors a great debt because I feel your broadcasts have done a great deal to counteract the anti-Semitic propaganda such as put forth by the Nazis and which would have the non-Jew believe that we are a tricky, conniving selfish race.

Jewish organizations, like the National Council of Jewish Women and the Anti-Defamation League, added their own testimonials in fan letters.

Those motivated to write to Goldberg invariably approved of the ethnic content of The Goldbergs, as well as its commitment to combining entertainment and education in “the big new field” of television.” People wrote as ambassadors and representatives of their faiths, civic organizations, and political parties. Defying the gospel of audience segregation preached by networks and sponsors, these listeners did not object to the politics of The Goldbergs. Instead, they celebrated what they saw as shared American values of curiosity, pluralism, and acceptance.

Although later criticized as being un-American by anti-communists, Berg was a fervent believer in the American Dream—the belief that anyone could succeed in the United States. But the series referenced an American dream grounded in New Deal–era beliefs in public institutions, particularly education. “The greatest opportunity” that immigrant families found in the United States, according to Berg, “was the chance to give their children an education. America was full of good and wonderful things and the schools were the best.” This American dream, moreover, was tempered by a working-class sense of community, one that insisted on mutual support and sharing. When Jake complains about helping to subsidize Molly’s relatives’ emigration to America to escape Nazism, Molly chides him: “No matter vhat anybody is got, dey got trough de help of somebody else. By ourselves ve couldn’t make notting. You know dat, Jake.” As Berg put it in an interview, “when you live in a nice home and ride in nice cars, you forget that thousands of families live huddled up in two-room tenements.” Berg vowed to never forget the economic disparities around her or the fact that “By ourselves ve couldn’t make notting.”

The thousands of letters variously addressed to Gertrude Berg, Molly Goldberg, the Goldberg Family, the networks, and sponsors highlight the attachment listeners felt to the series, undermining anti-communists’ conjuring of an angry conservative audience committed to boycotting products. But anti-communists’ threats worked seamlessly, since few individuals, groups, or organizations were in a position to publicly challenge what quickly became an industry-wide form of common sense. However distasteful networks, advertisers, and anti-communists may have found the content of The Goldbergs, the thousands of fan letters Berg received suggest that listeners and later viewers didn’t necessarily agree with them. Rather than being a reflection of audience desires, the show’s cancellation—and the blacklist as a whole—was a projection of producers’ own prejudices onto an audience that they were in large part imagining.

—Carol Stabile is in the process of completing “Black and White and Red All Over,” a book manuscript about the blacklisting of women writers in 1950.