by Isabel Millán, Assistant Professor, Department of Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies

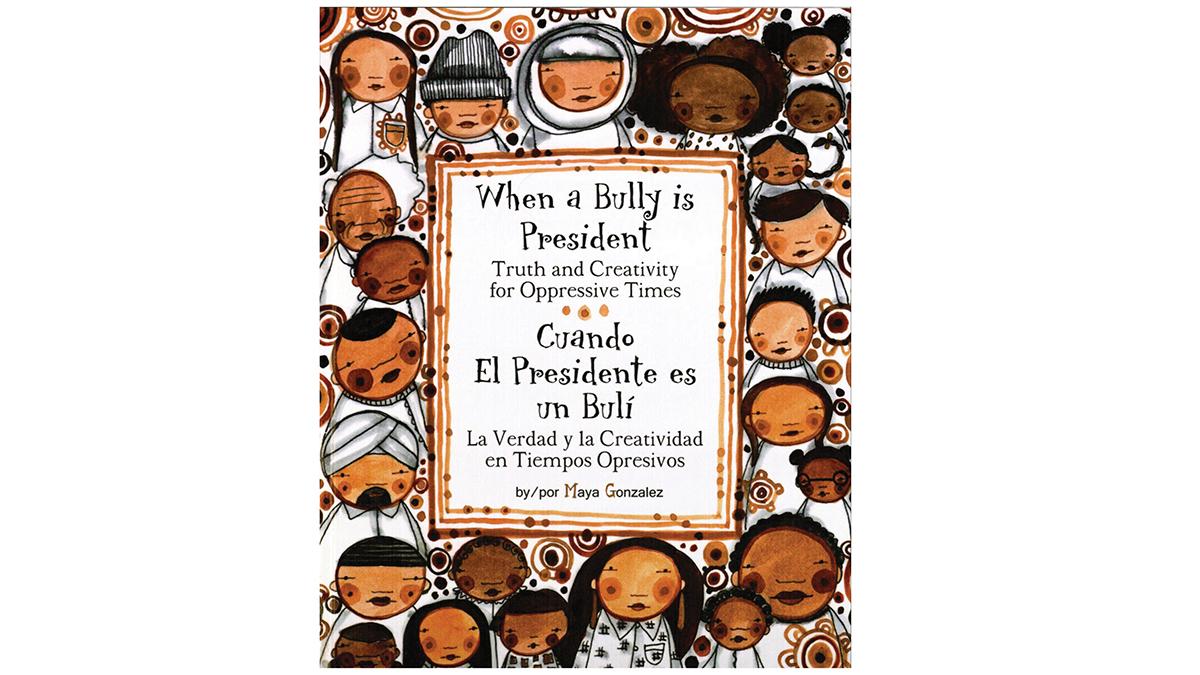

How might children’s literature help us respond to our current political climate? While all literature is politically (or at the very least, ideologically) motivated, a picture book that exemplifies political content for children is Maya Gonzalez’s When a Bully is President: Truth and Creativity for Oppressive Times.1 Not only is it an indirect comment on Trump but it also reframes US history through bully discourse in its reflections on colonization, slavery, war, and xenophobia. When read as political texts, picture books have the potential to inspire collective action or activism.

Gonzalez does not shield readers from social inequalities. Instead, When a Bully is President invites us to explore responses to bully history by incorporating social justice movements and creative expressions—or “truth and creativity.” This manifests as, for example, portraits of former US presidents with the number of enslaved people they had below them juxtaposed with references to civil rights activists such as Bayard Rustin alongside the current Black Lives Matter movement.

Unlike a more traditional picture book, this one does not provide a linear plot, nor does it include a protagonist or set of main characters. Rather, Gonzalez speaks directly to readers (second person point of view), telling them, “If you want to do something when a bully is president, here are some things…you can do on your own or with other kids.”2 The vibrant illustrations demonstrate these actions, including passing out flyers, creating protest signs, and marching, providing readers regardless of age with a type of activist roadmap. As evidenced throughout the book’s text and illustrations, Gonzalez’s version of politics for kids centers queer, feminist, crip, and BIPOC collective action. She includes strategic visual markers (e.g., pride flags or a trans symbol for LGBTQ+ visibility) while still allowing for ambiguity or fluidity depending on our needs as readers, or what I refer to as autofantastic reading.3

Picture books such as When a Bully is President inspire creativity by incorporating artistic possibilities within and beyond their pages. One exercise asks readers to draw portraits of themselves or other community members. Outside of the book, epitext features include coloring pages and additional drawing handouts.4 As described by Gonzalez, “This book is an opportunity to talk more about what’s going on, how it fits into the history of bullying in the US, and what we can do about it, while providing a structure to use our creative power to stay strong and focused on ourselves.”5 Whether one is painting “Standing with Standing Rock” on a poster or drawing themselves as a tree rooted in the ground, art has proven itself vital for political movements.6

Children’s literature is not only for children. It can teach all of us how to enact social change if we are willing to pay attention. I was able to do so with the support of a CSWS Faculty Research Grant.7 This research stems from my broader interest in BIPOC and LGBTQ+ children’s picture books, which I published as Coloring into Existence: Queer of Color Worldmaking in Children’s Literature (2023).

—Isabel Millán received a 2023 CSWS Faculty Research Grant for this project.

References

1 The original version, quoted herein, was published bilingually (English and Spanish) in 2017 as When a Bully is President: Truth and Creativity for Oppressive Times/Cuando el President es un Bulí: La Verdad y la Creatividad en Tiempos Opresivos (San Francisco: Reflection Press). The second edition was published monolingually in English.

2 Gonzalez, When a Bully is President, 19.

3 I theorize autofantasía and autofantastic reading practices within Coloring into Existence: Queer of Color Worldmaking in Children’s Literature (New York: New York University Press, 2023).

4 Some of these handouts are also included in the second edition of the book.

5 Quoted from Reflection Press; see https://reflectionpress.com/our-books/when-a-bully-is-president/

6 Protest or political art can include public art such as murals or graffiti to ephemera such as zines and posters. Examples abound across political movements. For artwork with the Chicana/o/x movement, see Guisela Latorre, Walls of Empowerment: Chicana/o Indigenist Murals of California (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008); Karen Mary Davalos, Chicana/o Remix: Art and Errata Since the Sixties (New York: New York University Press, 2017).

7 This research will be published as an article tentatively titled “When a Bully Is President: Children’s Literature for Oppressive Times” in the academic journal Feminist Formations (expected 2025).