by Yvonne Braun, Assistant Professor

Large-scale dam building continues to be promoted as a means toward economic and social development in developing societies—despite the persistent critiques of many social scientists, environmentalists, social justice advocates, and affected communities around the world. The Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP) is one of the five largest dam-development projects currently under construction anywhere. Designed as a five-dam mega-project between the governments of the Republic of South Africa and Lesotho, the LHWP has the primary objective of creating national revenues by selling water from Lesotho’s mountains to urban Johannesburg, South Africa. Tens of thousands of the Basotho people will be affected by it over a 30-year period.

My research documents the experiences of rural communities in Lesotho struggling to negotiate the multi-dimensional and contradictory consequences of this project. Small, resource poor Lesotho was in many ways an unlikely site for such a large project. At the same time, the $8 billion dollar LHWP was the “only” development deemed feasible for Lesotho’s bleak economy in the 1980s. How has the construction and implementation of a large-scale project affected the surrounding communities, and how are these consequences gendered, raced, and classed?

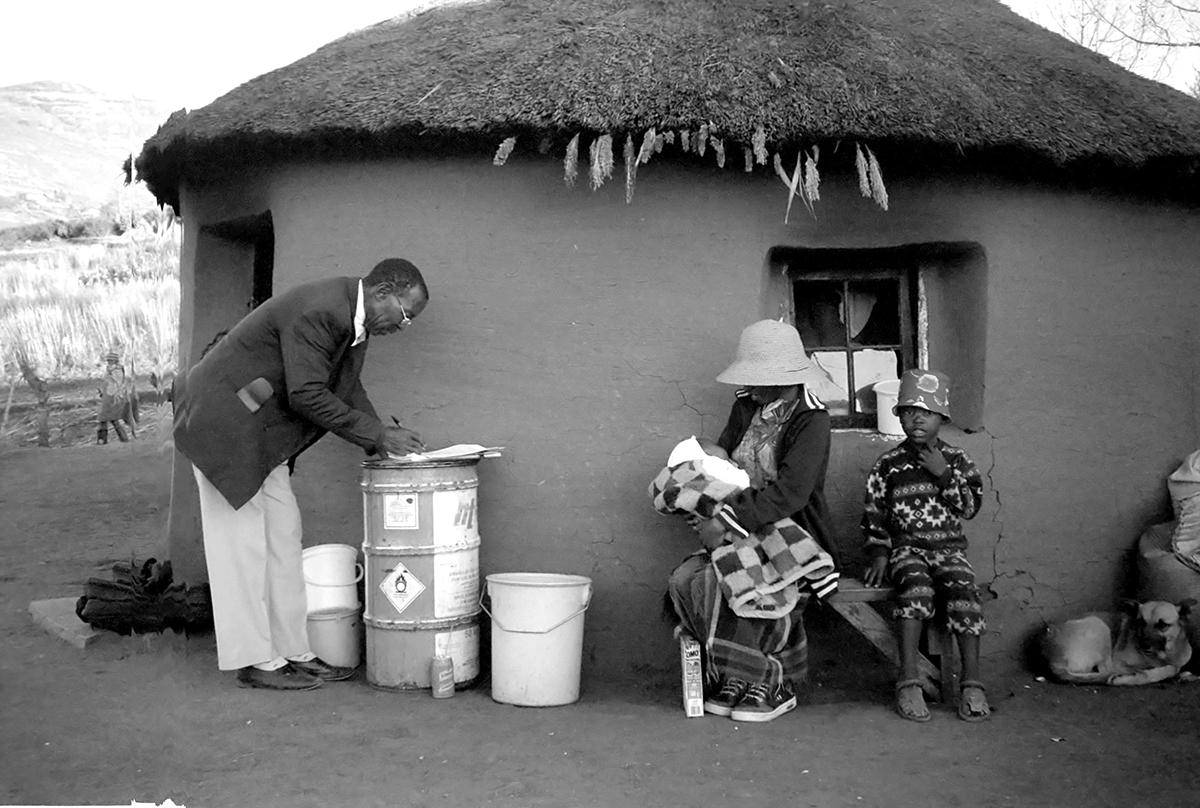

Local communities affected by the series of dams face resettlement, loss of agricultural and pastoral lands, loss of means of production, increased risk of impoverishment, and changes in access to natural resources such as wild vegetables, herbs, and medicines. These communities are also some of the poorest in the country, and, ironically, they absorb the bulk of the indirect costs of this form of development. In my thirteen years of research on the LHWP, I have found that rural poor women, in particular, absorb the costs of a changed landscape. They struggle to adapt, resist, and thrive while creatively negotiating the powerful and intimate changes in their lives. Their experiences are consistent with research on other contemporary dam-development projects of similar scale.

Specifically, Basotho women describe increased workloads, the burden of more household purchases, decreased nutritional status, less access to gatherable natural resources, and reduced access to compensation benefits from the development authority. For poorer women, these consequences created significant food insecurity, vulnerability to increased impoverishment, and increased reliance on cash. They were positioned to rely on informal work, such as domestic labor or sex work, as an economic strategy in order to access money at a time when the LHWP was intended to bring economic relief. In practice, the project has constricted women’s livelihood opportunities.

Funds from CSWS supported the development of three articles that drew from and extended my research in Lesotho. In the first article, I considered how the sites and social relations of large-scale development projects may create particular dynamics of inequality while reproducing gendered, classed, and raced privileges, despite the dominant development discourse promising local employment and poverty reduction. I centered my analysis on the social organization of work at one LHWP dam site. My two goals were:

1) to render visible the gendered, classed, and raced ways that bodies and labor are organized in the context of this mega-project, both producing and constituting global and local inequalities;

2)mto show how masculinities are mobilized hierarchically to privilege an international hegemonic masculinity over local masculinities, and how the gender order is largely maintained by excluding women from the “privileges” of development through keeping women second-class citizens.

These conclusions raise critical questions regarding the nature of the social organization of work at large-scale development projects, and how multinational projects may reproduce racial and gender inequalities at the sites of development.

The second article more closely examines the rise of sex work in the context of large-scale development. I found that non-elite women were able to access development monies indirectly through prostitution by positioning themselves as sex workers for foreign development workers. The increasing opportunities for sex work take place in a larger context where the devaluing of women's labor on farms and in households serves to exclude them from being legitimate receivers of “development.” The context reproduces male ownership and patriarchal authority, ultimately pushing some women into work that is precarious, low wage, risky, and often demeaning.

Local men benefit from the retooling of hegemonic masculinity. However, I also found that while the state advances the interests of Basotho men over those of women, it simultaneously marginalizes local men’s interests as it protects the interests of the new international hegemonic masculinity.

In a third article, I worked with co-author Michael C. Dreiling. We contrasted the sociopolitical contexts of large-scale development and the HIV/AIDS crisis in Lesotho in order to capture important historical conjunctures that expanded opportunities for the mobilization of women’s rights as human rights. We revealed how local women’s rights organizations, such as Women and Law in Southern Africa (WLSA), found greater support and resonance for women’s rights claims amid the sociopolitical context of the AIDS crisis. This occurred in marked contrast to the stifling of those same claims during a period of neoliberal, nationalist development initiatives in Lesotho.

The AIDS crisis in particular introduced new international actors who helped support a ‘frame bridging’ strategy whereby women’s rights were characterized as health rights. This strategy is rooted in a critique of the AIDS crisis that identified the role of gender inequality as an important driver of the epidemic. These links to transnational feminist networks as well as to international health agencies bolstered the critiques of gender inequality articulated by WLSA and other women’s rights advocates and helped usher in a series of very positive, but also very limited, legal changes in Lesotho in 2003 and 2006.

Contradictions, Consequences and Challenges

These three articles, generously supported by CSWS, point to the contradictions of internationally financed large-scale development. They show the tragic and ironic ways that rural poor women subsidize international development industry projects such as the LHWP.

My current research continues to render visible the lived realities of the raced, classed, and gendered consequences of neoliberal development in Southern Africa. It further articulates challenges to the dominant development industry and nationalist discourses about poverty, rural people, and the social and economic promises of contemporary large-scale development projects.

-Yvonne A. Braun is an assistant professor in the departments of women’s and gender studies and international studies. She can be contacted at ybraun@uoregon.edu.