Interviewed by Alice Evans, CSWS Managing Editor; Michelle McKinley, CSWS Director and Professor, School of Law; and Dena Zaldúa, CSWS Operations Manager

Winner of a 2017 Oregon Book Award for creative nonfiction for Angels with Dirty Faces: Three Stories of Crime, Prison, and Redemption, Walidah Imarisha also has edited two anthologies, authored a poetry collection, and is currently working on an Oregon Black history book, forthcoming from AK Press. Imarisha has taught in Stanford University’s Program of Writing and Rhetoric, Portland State University’s Black Studies Department, Oregon State University’s Women Gender Sexuality Studies Department, and Southern New Hampshire University’s English Department. She spent six years with Oregon Humanities’ Conversation Project as a public scholar facilitating programs across Oregon about Oregon Black history, alternatives to incarceration, and the history of hip hop.

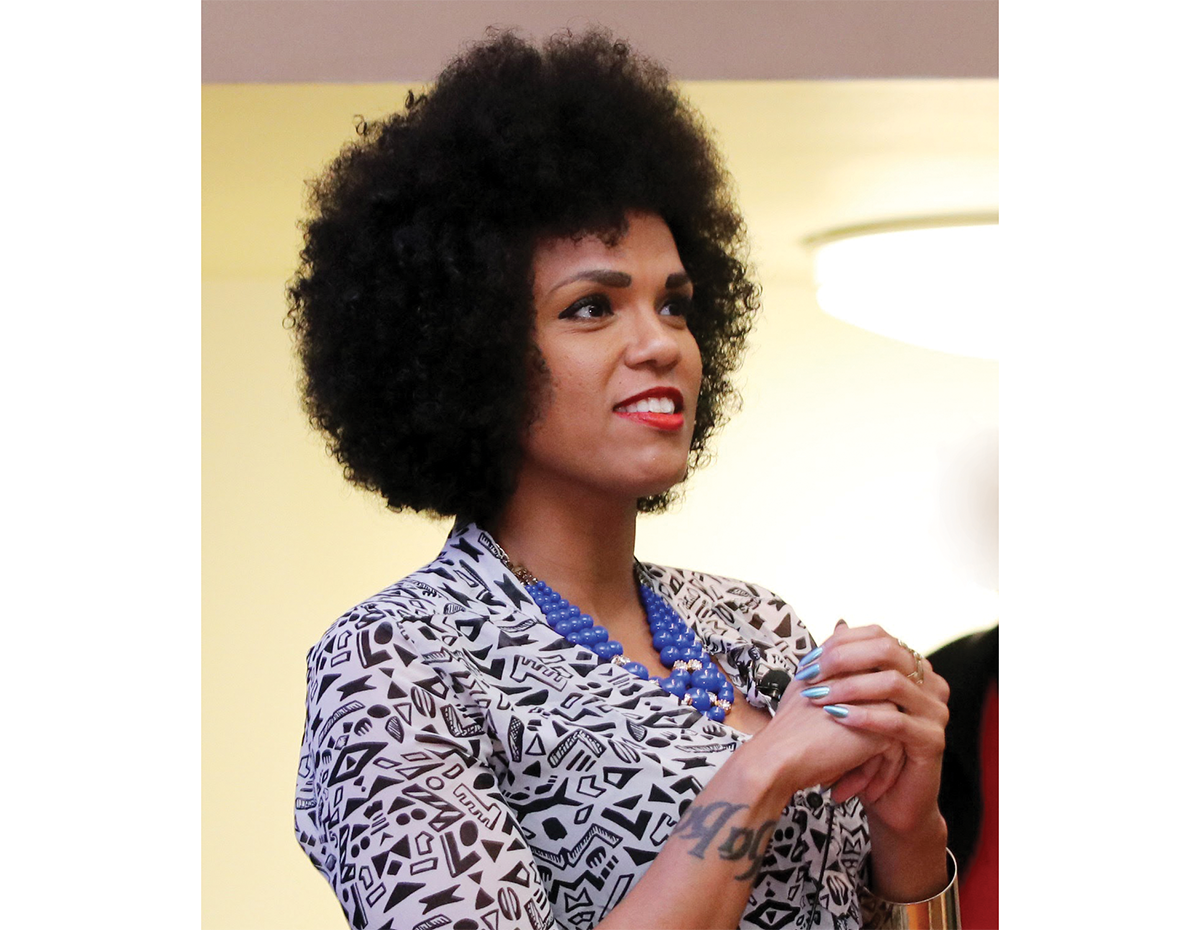

Speaking on the topic “Why Aren’t There More Black People in Oregon?: A Hidden History,” Imarisha addressed an overflow crowd of more than 300 people October 12, 2017, at Lillis Hall on the University of Oregon campus.

Q: One of the first things I read of yours was an essay in Oregon Humanities’ Beyond the Margins. I know you grew up largely on military bases overseas, and your mother was an educator who taught preschool. You were thirteen years old when you moved to Springfield, Oregon. And you were one of seven black students in Springfield High School. I read that you graduated at age sixteen. Was that from Springfield High School?

WI: Yes. But I wasn’t brilliant. I didn’t skip grades. I just said, I have to get out of here. I can’t do another year here. I’m either dropping out or I’m graduating early, ‘cause I have to go.

CSWS: From reading your essay, I understand that your high school guidance counselor suggested you go to Community Alliance of Lane County (CALC) for an internship. A lot of your radicalization toward social justice activism seems to have come from your experience of being in Springfield, an experience that perhaps fanned the flames of what may have already been there. I wondered if you could talk a little about that, since here you are back in the neighborhood again.

WI: The military disproportionately recruits people of color. Military bases are mostly folks of color, so, even though I was in Germany, the communities that I spent most of my time in were overwhelmingly brown. So it was quite shocking to move from that to Springfield, Oregon. At that time there was a lot of violence happening against students of color in Springfield, and also in Cottage Grove, where I also visited and spent time, with students of color getting attacked, a Latina student getting pushed down stairs while white teenaged men said, Go back where you came from. Things being printed in the school newspaper. It was an onslaught, and at that time, I couldn’t make sense of it. I didn’t understand why it was happening. I was lucky enough that I had a guidance counselor who gave me Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States. That helped me put it into perspective and steered me toward the social justice organizations CALC, and Communities Against Hate, and Youth for Justice.

CSWS: When you left, where did you go to college? What did you major in?

WI: Portland State University. I majored in history, and minored in black studies, which wasn’t a major at that time.

CSWS: How did you find your way into creative writing?

WI: I’d always been a writer, and before I learned to write, I would tell stories. My mom gave me one of those old school tape recorders with the slide out handles, so heavy you could knock someone out with it. She’d say, I can’t deal with you right now, just go and talk into your tape recorder. So there are hours and hours of me, hosting my own shows, interviewing myself, having my own variety shows. I still have some of those tapes. I recorded over them again and again, so there would be choppy bits.

CSWS: Your own radio show.

WI: Yeah, my own seven-year-old show. It was great; I loved it. I was a very talkative child. My mom said, I love you so much, but I just can’t listen to you anymore. I just need some quiet.

CSWS: You’re back now living in Portland?

WI: I’m in Portland for at least a year. I’m working on an Oregon black history book. I’ve signed a contract. I’m going to finish up the research, and get the writing done while I’m here.

I focus mostly on Oregon. In my Oregon History Timeline I do include nationally focused slides. Unfortunately you can’t assume folks have a working understanding of American history, and certainly not the history of folks of color in this country. With some people, I think, You lived through this, though, you should probably know …. And so, I have a slide about the Great Migration. I tried to include that in the framing, but I focus on Oregon.

I was thinking that the University of Oregon played a big role in the course of my life, because when I was still in high school, I went to hear an Oregon black history program here, by Dr. Darrell Millner, who was teaching at Portland State in the Black Studies Department, and it blew my mind. He was one of the reasons I wanted to go to Portland State, to study with him. I basically said, You’re going to be my mentor. And he was agreeable. That was very generous. I was lucky enough to come full circle and teach with him as a colleague before he retired. He’s one of the preeminent historians on the experience of black folks in Oregon.

CSWS: There were racially restricted covenants up until the forties in places in Oregon such as Lake Oswego … I still go there and it’s still “Lake No Negro.” I know of a case of six Latino men at a baseball game. They aroused suspicion because they weren’t cheering for anyone, and they were talking among themselves. It’s enough under Terry vs Ohio to raise reasonable suspicion that they’re here illegally.

WI: And as you say, it doesn’t matter that the law [on racially restricted covenants] was lifted. We know this. Laws are actually the smallest way that these rules of society are enforced. I used James Loewen’s book about Sundown Towns a lot, because I think his framing is really important. The way that sundown towns were enacted was through law, through custom, and mostly through threat of violence. You can remove the law, but there are still multiple mechanisms. He says, anytime there is an all-white town, there was violence enacted to maintain it. A lot of times, people say, I don’t know, we just don’t have any people of color. I mean, we’re really open. We want people to come. And it’s like, No you don’t. No, you didn’t. And folks of color got that message really clear after you enacted that in an incredibly violent way.

CSWS: Vagrancy laws, too. Even if they’re underenforced, they are still really frightening when you read them. Anybody, after 6 p.m., arouses suspicion.

WI: Or has the potential. Have you read Paul Butler’s Let's Get Free: A Hip-Hop Theory of Justice? I always talk to folks about the scene where he’s driving with the cop, and he’s like, He’s a good cop. And the cop says, Pick a car, any car, and within ten blocks I’ll find a legal reason to pull them over. That strongly makes the point that it’s not what you’re doing, it’s who you are. When I do my work around the criminal legal system, I say that. Prisons have nothing to do with what you do, and everything to do with who you are. It doesn’t matter. There are enough laws to be enforced strategically, so it’s up to the discretion of the two most important people in the criminal legal system, which is the cop, first, and then the prosecutor.

CSWS: All of this surveillance is built on the common sense of race, which presumes that brown people are illegal and black people are criminal. To counteract that, you have excessive compliance. Have you seen in Portland this rise of white nationalism on campus?

WI: There’s such a lack of historical memory. In the 1980s and ’90s, Portland was called the skinhead capital of the country. There was massive organizing happening everywhere, and there was massive counter-organizing that took a lot of different strategies from legal strategies—to outing white supremacists and getting them fired, to confronting them in the street and handling things.

CSWS: But you know, after the stabbing on the MAX train [May 26, 2017] there was really a lot of thoughtful dialogue about how that was not an anomaly … you have Nicholas Kristof saying this is the best of America and the worst of America on the same train. And there’s something to that, but then also there were the supremacist marches that took place. If you really look at history you’ll see that Portland has many white supremacists. Even though we think they’re in the East, there’s a reason that they’re drawn to Oregon. There’s the white supremacist constitution that they wrote, and all of this stuff. I think a lot of it has to do just with Oregon’s romance with itself, and its libertarian streak, which can always go both ways. We don’t want interference, but that means that everybody can do what they want and we won’t mind.

WI: I think the focus on legality sends us down a road that ultimately supports existing systems of oppression. Martin Luther King Jr. was breaking the law constantly. He was a criminal. He was arrested. That’s not how many of us frame him. And many, but unfortunately not enough, believe that those laws were unjust, unfair, and should have ended. I think when we focus on legality and argue around whether this is legal or not, we’re actually missing the opportunity to talk about how we can deeply transform society.

CSWS: Could you tell us about your visionary fiction, about envisioning a future that is different from what we’ve had. And also about your work with prisoners. You call yourself a prison abolitionist. You also talk about “sustained mass community organizing.” Tell us about that within the context of what we’re discussing.

WI: I’ve been doing work around prisons since I was fifteen years old … it was when I was working in Philadelphia with the Human Rights Coalition, which is a coalition between prisoners families and former prisoners working to change the prison system, and we were fighting so hard just to maintain the status quo, and to not have things get any worse. It’s incredibly difficult, demoralizing as well, when you’re exhausted and you’re fatigued, and you say, We won, things are just as messed up as they were before, but they’re not more messed up. I was lucky enough to encounter folks who were incarcerated who were thinking about prison abolition, and other folks on the outside, and I began reading about it and realizing that we have to have a vision for what we want, and we have to start building that now.

In a linear progression, the idea is that first you dismantle something, then you build something else. We can’t actually do that. Because we can’t get anyone to dismantle something without presenting an alternative, but I also think that that work of building is the piece that gives us hope, and vision for the future, and empowerment, and it is also the piece that makes us all responsible for the future.

It’s often not easier but there becomes less personal responsibility when you’re resisting an existing system that other folks are also saying is a terrible system and needs to go. Then, you’re creating tactics.

But when you’re saying, I’m taking responsibility for the future, What is the future that I want? And then you also have to think about, Who do I need to be, to be able to build this future and then live in it? And that involves both internal and external changes. That’s really the space where true transformation begins.

As a prison abolitionist, I also think that prisons make us less safe. I believe that we need to be creating really different systems to hold people accountable and to heal communities when harm is done.

I have found science fiction to be, as my coeditor adrienne brown says [coeditors of Octavia’s Brew: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements, AK Press, 2015], a perfect testing ground. We have all been so ingrained [with the belief] that prisons have to exist, that we cannot have order without prisons, that saying to someone, I believe in abolishing prisons, and they’re like, Why are you now speaking Klingonese? What are you talking about?

But instead, you say, Okay, we’re now a hundred years in the future, and there’s been a nuclear holocaust, how are we going to deal with people who do harm? Or, Hey there’s an alien race, and there are these social inequalities happening. How do they deal with, you know…. People are more than willing to suspend what they know in science fiction. Because science fiction not only allows you to do it, it demands that you suspend everything you think that you know, and it creates this open space where folks are only constrained by the limits of their imagination.

The important piece is that we have to bring that back home, then. Especially when we talk about race. A lot of folks recognize that these things are talking about race, like X-Men is a metaphor for the status of people of color in this country. And I say, It’s absolutely a metaphor for the status people of color and other marginalized communities in this country. And, we can go there, but we’ve got to bring it back. Because a lot of people are really comfortable with it being over there and saying, Well, you know, I’d be in solidarity with mutants. And I’d say, Well, what about the black folk, though. And people are like, Ummmm.

It’s a way to open folks up, but especially if we’re talking about race, white folks are still going to have to do their work. And they’re going to be uncomfortable, and it’s going to come back to this planet, and it’s going to come back to this community, and it’s going to have to come back to their home. But having expanded, I hope they’re going to be able to see systems of oppression, rather than just hearing, You’re a terrible person. Which is often what happens, when conversations about race start to take place.

CSWS: I wanted to ask about a comment you made earlier, how Oregon keeps calling you back, and how you keep coming, and I would love to know, what is it that brings you back to Oregon?

WI: I think it’s the community I built. When I was in Portland, going to undergrad, I made some really strong connections that have continued to this day, personal as well as organizational and community connections. Especially once I started doing the Oregon black history work, the resistance and resilience of communities of color here, and for me personally especially the black community, is something that has called me back, because I think how hard people fought to be here. I think about folks hearing, we will whip you, every six months, thirty-nine lashes, if you are black, until you leave this territory. And 124 black folks heard that, and said, We’re staying then. And the courage, and determination, and sheer stubbornness that must have taken. And if they hadn’t done that, I would not be here. There would be no people of color in Oregon, as it was planned. It would be the racist, white utopia free of people of color that was the founding notion of it.

Seeing the ways that communities of color have been controlled, contained, exploited, and brutally kept so small, and yet have continued and always existed and always resisted is something that has been immensely inspiring, and it’s definitely what I am trying to frame the book around. I am framing communities of color as the active change makers that they are, who’ve made the state, this country, and this world better for everyone through their courage. So, especially once I started doing that work, and connecting with other people doing that work, both academically as well as on the community level, I felt very invested in wanting to be a part of that history and that legacy.

CSWS: You describe yourself “as an historian at heart, reporter by (w)right, and rebel by reason.” Could you tell us how you came up with your framing, because we love it.

WI: My former band member came up with it fifteen years ago, a long time ago.

CSWS: What band?

WI: Puerto Rican Reconstruction … a Puerto Rican punk band in New York that I did work with. So I kept it … everything else in the bio has changed, and it’s up front and I like it. Now is not the time to couch our stances. It is a time to speak clearly and forthrightly. I think objectivity is a fallacy, always, and I think right now the attempt to project objectivity can make us complicit in death.

And so, I’m working to be very clear. adrienne always says, all art advances or regresses justice, and I’m very clear which side of that dichotomy I’m on. I feel like five years ago people would have at least said publicly that they believed in certain things, but now people say, Really, can we? Maybe I don’t believe it, but it’s free speech.

CSWS: That’s something my friend was talking about yesterday, that on campus, white nationalist groups have become emboldened, and are putting up flyers and so forth. He said that some of the antifa [antifascist] students now feel like they have to hide, and they can’t be open, speak openly, because they’re afraid of the backlash that they’re going to get from the fascists, who are going to make their life hell.

WI: For me, more than antifas, folks who have privilege in these societies, and who have social capital. Some of the professors need to be standing up and saying, I’m antifa. Elected officials who believe in being antifascist have to say, I’m antifa. We cannot use academic speak to hide behind anymore. We don’t have time for that.

CSWS: We were discussing this a year ago with Cherríe Moraga. She talked about, Well, I teach at Stanford, but I’m so done with making people feel inferior by hiding behind this academic jargon and speak that we do. We need to actually speak to people in a way that they understand, and where we can have a conversation. I’m not hiding behind that anymore.

WI: I absolutely agree with that. About accessibility. And also where this information production happens, which is in communities that are oppressed, and then the academy reaches out, and basically makes you become a serf to pay for a degree to learn the things you already know.

But for me, I think it’s about saying again the old labor song, Which side are you on? There is no middle ground here; there’s no middle ground around white supremacy. Or white supremacists. Or anti-white supremacists. You can’t be a non white supremacist. A non racist. A neutral. There is no neutrality in these circumstances of humanity. I feel like we have to challenge that.

I also feel like we need to control the narrative. I refuse to have conversations about freedom of speech. Because I say none of this is about freedom of speech. And I’m not having a conversation. I start talking about white supremacists. You want to talk about freedom of speech, that’s great. You can have that conversation somewhere else. But that has nothing to do with what we’re talking about right now. We’re talking about white supremacist fascism. And I’m going to continue talking about that. And if you’d like to talk about that, please do. If not, please feel free to leave, and have your freedom of speech conversation somewhere else.